« older | Main Largehearted Boy Page | newer »

March 3, 2014

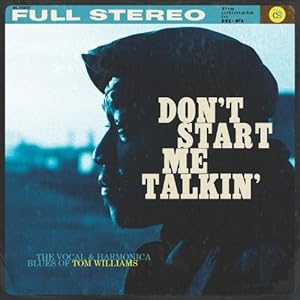

Book Notes - Tom Williams "Don't Start Me Talkin'"

In the Book Notes series, authors create and discuss a music playlist that relates in some way to their recently published book.

Previous contributors include Bret Easton Ellis, Kate Christensen, Kevin Brockmeier, George Pelecanos, Dana Spiotta, Amy Bloom, Aimee Bender, Myla Goldberg, Heidi Julavits, Hari Kunzru, and many others.

Tom Williams' Don't Start Me Talkin' is a masterfully told tale of the blues, authenticity, and identity.

Booklist wrote of the book:

"A splendid journey of a lifetime spent on the road—and the toll that it takes—[...]turn[ing] a difficult life into something quite joyous. Williams gets the details right too, such as searching for clothes in “two-for-a-dollar” bins in tacky stores. A humorous, picaresque blue note of a novel."

Stream a playlist of these songs at Spotify.

In his own words, here is Tom Williams' Book Notes music playlist for his novel, Don't Start Me Talkin':

Any reader remotely familiar with blues artists of the last century will know at first viewing my novel, Don't Start Me Talkin', that there's already a playlist built in: the twelve chapters (and the novel itself) each bear the title of a Sonny Boy Williamson song, from "Good Evening Everybody" to "One Way Out." It wouldn't be a mistake to think that while I was composing the book I was listening to these very songs, hoping that the vitality, wit and, well, ruckus of Sonny Boy's incomparable lyrics and ineffable harp playing would transmit through my fingers into the prose I tried to fashion, and in the characters I created: Brother Ben, the Last True Delta Bluesman (AKA Wilton Mabry) and Silent Sam Stamps, his harp-player (born in Michigan with the name Peter Owens). But since I've already rode on Sonny Boy's back a while, I thought it wise to share another few songs by other blues artists, two of which "appear" in the novel and others which certainly aided and abetted my composition.

Here goes:

"Say Man," Bo Diddley

It might be difficult to consider either Bo Diddley a bluesman or his music blues; he so clearly embodies early rock and roll: primal, raw, hypnotic. But this particular number, with its vaguely Latin rhythm beneath Bo and his maracas player, Jerome Green, trading insults, is one of a kind. These days, the insults seem rather tame—"At least my mama didn't have to put a sheet over my head so sleep could slip up on me"—but the absolute glee displayed in Bo and Jerome's attempts to top one another was often in my ears and imagination while I wrote the exchanges that my two principal characters, Brother Ben and Silent Sam, engaged in between sets and while on the road. I'll never write a line as perfect as any of Bo's or Jerome's—"That girl was so ugly, she had to sneak up on a glass to get a drink of water"—but I certainly tried to capture the mirth and mischief—and begrudging respect—so endearingly captured on this track.

"Conjur Man," Memphis Minnie

One of the recurring riffs of my novel is blues artists and their names. Neither Brother Ben or Silent Sam came into the world with those names, and neither did Memphis Minnie (who was born Lizzie Douglas in Algiers, Louisiana). I name check her early in the book out of my great affection; I rather wish—as I do with most of the artists in my various roll calls in the book—her life story were better known; it' as entertaining as any fiction. But this particular song points to another riff of the novel: cons and conjures. At more than a few points in the novel I try to endow Brother Ben with qualities of the conjure man—that is, he might be more than just a skilled con man. Sometimes Peter thinks he's got control of more than the strings on his guitar, even though Ben's roots medicine is found more in green tea and herbal supplements. And if you haven't heard Memphis Minnie ever, this tune—with its haunting guitar and Minnie's heartbroken plea that she's got to find the conjure man now—will certainly cast the right kind of spell.

"Preaching the Blues," Son House

On more than one occasion, characters attempt to get Ben to explain just what the blues are. In Chapter Three, he talks of how the first bluesman might have been a preacher who lost his faith. Eddie "Son" House, contemporary of Robert Johnson and Charley Patton, made abundantly clear the related motives of the bluesman and the preacher in this wonderful bit of sacrilege: "I'm gonna be a Baptist preacher, so I won't have to work." A lot of times, when I listened to Son House, I'd keep this song on repeat, because it points out an overlooked aspects of many blues performers: a lot were funny as hell. Listen to the sequence in this song where Son evokes a series of sinners confessing and try not to see this humor as necessary a part of the blues as evil-hearted women and black cat bones.

"Special Streamline," Bukka White

At one point in the novel, Peter, the narrator, chafes against the notion that many hold about blues being played by bad men, how that fits too neatly into the narratives about bluesmen and African American males, in general. Booker Washington White, or Bukka, could be considered a bad man—he served a prison term in Parchman Farm for assault—but you could never tell this from listening the "Special Streamline": it is a blues classic, a train song, yet an undeniable lightness imbues it. White's bottleneck playing is more chiming and precise than the slurring drone you hear in the work of someone like Elmore James (a master himself). His voice is easy, amiable, as he calls out stops along the way of the "special streamline coming out of Memphis, Tennessee," and he sounds a man at ease with himself, confident in his cadences. You sense—or maybe it's just me—a smile on Booker T. Washington White's face as he sings this. And that very joy—an emotion we don't always expect with blues of any kind—is one of the qualities I wanted to bring to this book. For at some point in time you have to have felt this good to know just how low down low down can be.

"Cherry Ball Blues," Skip James

Skip James's real name: Nehemiah Curtis James. He recorded this song in 1931. And like many of the Mississippi performers of his day, he recorded, saw little money from that, then faded into obscurity, trading blues, perhaps, for the pulpit.(See above: House, Son. "Preaching the Blues.") Brother Ben uses "Cherry Ball Blues" as a way to clear out the room during the impromptu jam sessions that often crop up after his and Silent Sam's concerts. I wanted to use it as a way of showing how dexterous Ben is, both as a guitarist and as a "player" of people. It's so complex a tune, out of keeping, in many ways, with what most consider to be Delta Blues, though James grew up in Senatobia. More than anything, the song, for me, points to the curious multiplicity of blues: just as you start to think you know everything about it, you hear a tune like this, and learn more about Skip James (and recall that you heard Cream cover his "I'm So Glad") and realize, yeah, there's so much more you have to learn. I felt this as I wrote the book and transferred a lot of that anxiety to Peter, who is often struggling to follow along with Ben as much as the fans trying to play along with "Cherry Ball Blues."

"Key to the Highway," Little Walter

Walter Jacobs (a name that could be that of your tailor, or your accountant), better known as Little Walter, could have very well occupied the space that Sonny Boy Williamson II does in Don't Start Me Talkin'. I might have had to name it "Juke" or "Boom, Boom (Out Go the Lights)". Both were brilliant harpists, both were wonderful performers, but, as Peter says in the novel, he "takes his cues from Sonny Boy, who lived a mighty long time." Little Walter died in his forties. But this particular number, though it is not referenced in the book, guided me day after day in the writing. The book, after all, is a road novel, and this song, which was already a well covered number by the time Walter got to it in 1958, contains some of the finest hitting the road lyrics ever:

I got the key to the highway

Billed out and bound to go

I'm gonna leave here running

Walking goes too slow

I'm going back to the border

Little girl, where I'm better known

'Cause you haven't done nothing

Drove a good man away from home

And in quoting these lines, I'm reminded of a feeling that accompanied much of writing Don't Start Me Talkin': How can I ever top that?

Tom Williams and Don't Start Me Talkin' links:

video trailer for the book

excerpt from the book

excerpt from the book

HTMLGIANT review

InDigest review

Kirkus review

Patricia Ann McNair interview with the author

Superstition Review interview with the author

WMKY interview with the author

also at Largehearted Boy:

Book Notes (2012 - ) (authors create music playlists for their book)

Book Notes (2005 - 2011) (authors create music playlists for their book)

my 11 favorite Book Notes playlist essays

Online "Best of 2013" Book Lists

2013 Year-End Online Music Lists

100 Online Sources for Free and Legal Music Downloads

Antiheroines (interviews with up and coming female comics artists)

Atomic Books Comics Preview (weekly comics highlights)

Daily Downloads (free and legal daily mp3 downloads)

guest book reviews

Largehearted Word (weekly new book highlights)

musician/author interviews

Note Books (musicians discuss literature)

Short Cuts (writers pair a song with their short story or essay)

Shorties (daily music, literature, and pop culture links)

Soundtracked (composers and directors discuss their film's soundtracks)

weekly music release lists