« older | Main Largehearted Boy Page | newer »

September 1, 2015

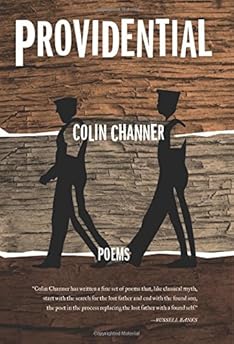

Book Notes - Colin Channer "Providential"

In the Book Notes series, authors create and discuss a music playlist that relates in some way to their recently published book.

Previous contributors include Bret Easton Ellis, Kate Christensen, Kevin Brockmeier, T.C. Boyle, Dana Spiotta, Amy Bloom, Aimee Bender, Jesmyn Ward, Heidi Julavits, Hari Kunzru, and many others.

Colin Channer's poetry collection Providential is a stunning debut.

Booklist wrote of the book:

"Jamaican-born Channer draws on the rich cultural heritage of the Caribbean and his own unique experience for this energetic, linguistically inventive first collection of poetry....Channer's lyrics pop and reel in sheer musicality, reveling in the colorful, conflicting crowd, from passive Rastas to seemingly countless acts of police violence....A dextrous, ambitious collection that delivers enough acoustic acrobatics to keep readers transfixed 'till the starlings sing out."

Stream a playlist of these songs at Spotify.

In his own words, here is Colin Channer's Book Notes music playlist for his poetry collection Providential:

Providential is my first collection of poems. In it I look hard at difficult stuff — policing, family, violence, loss. Somehow in the writing, my gaze remained tender and my hearing stayed receptive to the joke. On a basic level, Providential is a book about Jamaican police, a literary figure last tackled in 1912 when Claude McKay released his Constab Ballads.

In making these poems over 100 years after McKay published his, I drew on my own grounding in Jamaican culture and my complicated relationship with my dead father (a Jamaican cop). I also drew on the sounds of Jamaican English and American dialects, especially the ones in New York, where I moved to at 19, and lived for more than twenty years.

I write mostly in silence. But because reggae is a vital part of my literary esthetic it directs and guides this book. I admire this music that came into its own in the early 1970s and created a space for itself in the pop domain. I admire it for finding expression beyond the comedic in Jamaican patwa and English. I admire the soul force it took on after absorbing the communitarian philosophies and people-centered politics of Rastafari. This was the music's great transgression—taking the acoustic drummed, resistance of the hill-dwelling Rasta hermits electric. By putting the people's honest claim to equal rights and justice on the jukebox, by pointing to plantation boundaries as proof of structural violence, by simply loving Africa, reggae was set on by state agents—police. If this seems strange to you then you have no idea how colonialism works.

The word "babylon" in the reggae lyric refers to more than just "the system." It's a nickname for police. I can't think of a single pro-cop reggae lyric. I can't think of a single lyric that is even nuanced when it comes to (another nickname) "the beasts." But I am descended from cops on both sides and in this book I'm operating as a poet. And nothing undermines a poem more than righteousness, even if that righteousness is elsewhere, off-page, earned.

In reading through Providential now, I recognize its songs. Some had been there always, drying. Some have come to roost.

"Police and Thieves" by Junior Murvin

Providential's working title was "Police and Thieves" — the reggae original; not the punk do-over. It’s a track I’ve always liked. Deep and dubby. Fat-bottomed with some sketchy wah-wah and spacey phasing on the guitars. Junior Murvin is pure Curtis Mayfield cool here. Mentholated. Breezy. The great Lee "Scratch" Perry knew how to get the best out of singers, musicians and songs.

"The Harder They Come" by Jimmy Cliff

Film director Perry Henzell figures in the opening poem "Revolutionary to Rass." The name is taken from a line delivered by Jimmy Cliff 's character Perry's movie "The Harder They Come." This film is a deeply idiosyncratic depiction of structural violence in Jamaica. On screen we have the cops against the poor and the Christian's fighting down the Rastamen. Still, this title is pure feel-good, upstroked pop. If you're feeling underdoggish, put it on. Get yourself revved up.

"Ethiopian Serenade" by The Mystic Revelations of Rastafari

The second poem is a meditation on the emotions of the first men who signed up for the force in 1867. It couldn't have been easy for them. They were black men forming a squad only two years after white and near-white militias slaughtered a thousand or more black peasants after a revolt. "Ethiopian Serenade" is a masterful elegy of classic Rasta drumming overlaid by jazz-inflected saxes and flutes. The recording is let's say artisanal, which adds to its tone.

"1865" by Third World

This mellow-vibe tribute to the leader of the peasant uprising was in my head as I wrote the poem "Lea" — which is about a survivor of a massacre that followed the revolt. He is both a boy and an elder in the poem. A version of my mother appears as his great-grandchild. The need and capacity to have beauty in tribulation is one of reggae’s great thrusts.

"Leggo Me Hand Gate Man" by Josey Wales

This is a pulse-raising toast to outlaws. Policing in Jamaica shares many of the patterns of clan violence. The poem "Clan" gives Kingston’s gangsters their due. Josey Wales, self-named for a character played by Clint Eastwood in a western, is let’s say a man of influence on the mike and off. His narrative of badding up a bouncer outside a dancehall is detail flecked and strangely comic. The bass line is one of the first ones I learned when I bought my Fender.

"Freedom Sounds" by the Skatalites

The poem "Occupation" is a portrait of a neocolonial old ex-policeman and his nostalgia for the days of ska. In his mind ska means order and reggae its opposite. I kept a soft spot for the anxious lower middle class while making the poems in this book. This is pretty much as far as a cop could rise. The ska men with their suits and music sheets embodied decency. My mother loved ska. Eventually, I did too.

"Theme From Shaft" by The Chosen Few

This reggae cover is accidentally comical in so many ways. The good news is the groove is undisturbed. It's in many ways just a laid-back version of the original with local dudes doing their best to Yank it. The Roundtree film is referenced in the poem "Funeral" — an elegy for a charismatic vigilante cop named Porter: "Mimic of seventies westerns and gang epics …" Riiiiide awwwn ...

"Good Morning Jah" by Rita Marley

There is so much soulful sweetness and gratitude for life in this direct address to the Rastafarian god. In listening to it I can't help thinking of how it makes a strange complement to the scatological poem "Porter's Prayer" in which a vigilante cop prays for protection, beginning with: "Whoever whater/the fuck you are ..."

"Four Women" by Nina Simone

The elliptical female voice at the center of the poem "Intermezzo" tries to contain itself as it addresses a policeman sent to take a statement after a rape. I hear a similar struggle for dignity and rage-control in Simone's moving song. Whereas my speaker doesn't feel she can talk directly about the crimes against her, Simone's speakers do, especially the last one, Peaches, who growls why she's "... awfully bitter these days ..." This is a hard song to listen to. This was a hard poem to write.

"Rapture" by Blondie

I used to dance to this cut at the Paradise Garage back in the day. It makes me think of bodies free styling. New York was outlandish in those days—the early eighties. The poem "On a Dry Field in Nowhere" is my gun salute to bodies making magic moves on fields and courts.

"Shank I Shek" by Bobby Ellis

"Shank I Shek" is the people's "Taps" or "Last Post" in Jamaica. When this dirty horn classic comes on people get deep into themselves, remember their dead. They also rub up on each other and otherwise get on bad when a selector drops this classic in a party or dance. The poem "Balls" is based on a memory of seeing a teenage gunman's corpse outside the national stadium. It wasn't chalked or covered. The cops and soldiers were casual in attitude, just hanging out, standing round. When I think of the poem or the moment that inspired it something opens in my head and this song comes on.

"Drive Her Home" by U Roy and Hopeton Lewis

This risqué call-and-response number was a hit before my time. I used to hear it in rum bars with my dad. He’d have a white rum chased with milk and I’d have a copper-colored Kola Champagne. Although I didn’t understand the lyrics I felt something happen in the room every time someone punched it on the and it came on. "Corporal Teego Brown Tells Us What Every Bartender In Jamaica Knows" is partly inspired by remembered smells and feelings on early seventies bar life and this song.

Ascenseur pour l’échafaud by Miles Davis (the album)

The middle of book is anchored by a longish suite: "Fugue In Ten Movements" — to my mind a filmic poem. Listening to this album gave me the sense that I was in touch with a reference note for lonely. Listening to it over and over again, taught me something about how to keep loss as a current in a varied whole that sometimes swings upbeat. Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers are genius here.

"Stalag 17" by The Techniques All Stars

The poem "General Echo Is Dead" is a tribute to one of many Jamaican music figures killed by police. "Stalag 17" arbitrarily named for a 1950s war film is the dub track under Echo’s monster hit "Arleen". It's also under Muma Nancy’s "Bam Bam" and Tenor Saw’s "Ring the Alarm". The bass is stiff. The organ churchy. So much blues in the guitar.

"Michael Talbot Affair" by Keith Hudson

I heard strains of this dub track in my head while writing "Knowing We'll Be Mostly Wrong" -- the second to last poem in the book. Sometimes a poem begins with just a tone. It's as if the tone creates the white you write on in your head. This poem is addressed to my father, and it's about how tough it is to raise kids. There's more than a hint of "House of the Rising Sun" here, but this track is its own thing, a path that shadows a main.

"Turiya And Ramakrishna" by Alice Coltrane

The final poem gives the collection its title. It's 13 pages long, looping but clear. It begins in Rhode in the present then roams across time and location, shifts into dream logic then returns with a strong commitment to the world of gravity pulling on nouns. Like the song, the poem tends toward the lush and melancholy. Is unconsciously a blues. This poem and this song make me weep.

Colin Channer and Providential links:

New York Journal of Books review

Publishers Weekly review

Read in Colour review

Tallawah review

also at Largehearted Boy:

Book Notes (2015 - ) (authors create music playlists for their book)

Book Notes (2012 - 2014) (authors create music playlists for their book)

Book Notes (2005 - 2011) (authors create music playlists for their book)

my 11 favorite Book Notes playlist essays

100 Online Sources for Free and Legal Music Downloads

Antiheroines (interviews with up and coming female comics artists)

Atomic Books Comics Preview (weekly comics highlights)

Daily Downloads (free and legal daily mp3 downloads)

guest book reviews

Librairie Drawn & Quarterly Books of the Week (recommended new books, magazines, and comics)

musician/author interviews

Note Books (musicians discuss literature)

Short Cuts (writers pair a song with their short story or essay)

Shorties (daily music, literature, and pop culture links)

Soundtracked (composers and directors discuss their film's soundtracks)

weekly music release lists

Word Bookstores Books of the Week (weekly new book highlights)