« older | Main Largehearted Boy Page | newer »

April 5, 2016

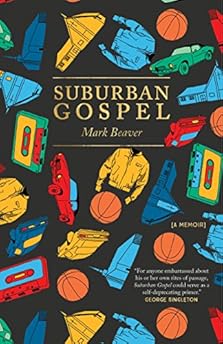

Book Notes - Mark Beaver "Suburban Gospel"

In the Book Notes series, authors create and discuss a music playlist that relates in some way to their recently published book.

Previous contributors include Bret Easton Ellis, Kate Christensen, Lauren Groff, T.C. Boyle, Dana Spiotta, Amy Bloom, Aimee Bender, Jesmyn Ward, Heidi Julavits, Hari Kunzru, and many others.

Mark Beaver's Suburban Gospel is a moving and often funny memoir about growing up as a fundamentalist Christian in the American south.

Booklist wrote of the book:

"A backsliding evangelical Christian shares stories of a warped youth spent shedding religion for adolescent shenanigans in the 1980s. Never preachy or self-righteous, Beaver praises the exhilaration of independence while keeping faith always within reach."

In his own words, here is Mark Beaver's Book Notes music playlist for his memoir Suburban Gospel:

It is a tribute to my adolescent ingenuity that I conceived a foolproof strategy for keeping my parents out of my room: I plastered my walls with Prince posters. My father found particular offense in these glossy images. Because he was a Baptist deacon whose musical tastes ran toward the Florida Boys and The Inspirations—gospel groups who sang of Beulah Land and restricted their bodily movements to innocuous toe-tapping—Dad possessed no firsthand knowledge of Prince's raunchy tunes about incest, fellatio, and unfaithful girlfriends falling for other women. He didn't need the details. Prince's mere appearance was enough. In his worldview, no self-respecting man would dare broach a space enshrined to a prissy waif wearing high heels, bikini briefs, and a pompadour.

Initially His Royal Badness and I made an odd couple. He was black; I was white. He stood five-seven in heels; I was six-two in Converse Chucks. He played 26 instruments; I had abandoned baritone in eighth-grade. But mostly there was the matter of his blatant sexuality: a minister from a nearby congregation conducted an album burning in his church parking lot and commenced the festivities by dousing a vinyl copy of Prince's Dirty Mind in lighter fluid.

But throughout the 80s Prince and I wrestled with the same conflict between the sacred and the secular. For all his preoccupation with sex, Prince was equally obsessed with God. His music became the soundtrack for both our struggles to reconcile faith and flesh.

"1999"

From the intro, when our hero cryptically announces his intentions—Don't worry, I won't hurt you…I only want you to have some fun—I was drawn into a carnal world that threatened to undo every sermon I'd ever heard in one fell swoop. When I listened, I had to close my bedroom door, turn the volume down low, and huddle against the stereo speakers, as though I were hoarding a stash of particularly smutty porn. I was supposed to feel guilty, but it felt so good.

One night my girlfriend Yvette and I were listening to the title track while news of a tornado warning spread across Atlanta's metro area. Outside, the alarms sounded in the distance. The wind was gathering in great gusts of fury, the shrubs in the yard were bending under the force, and the whole house seemed to be shaking on its foundations. I should've headed home an hour ago, when the first reports of bad weather had come through the radio—but now it was too late to risk the roads and all we could do was sit tight and wait it out and hope the house stayed on the ground. So we just hunkered down and listened to Prince telling us Everybody's got a bomb/ We could all die any day.

Probably every American kid recognized what Prince was talking about. We were accustomed to hearing how the press of a button could end our lives. We'd seen that red splotch on Gorbachev's head. We'd squeezed under enough school desks to know nuclear annihilation was possible.

But when he segued into that chorus and sang, They say 2000 zero zero party's over, oops out of time/ So tonight I'm gonna party like it's 1999, I felt like I had special insight.

I was a Baptist boy, and knew my book of Revelation. I was well acquainted with the possibility the world could end at any moment.

I believed him.

"Dirty Mind"

After hearing 1999, I went back and bought the first four albums in Prince's discography, including Dirty Mind, a 30-minute middle finger to "society and all its games." Pulsing with funky synths and propulsive rhythm guitar, the album perfectly captured the growing tension between the Southern Baptist church's narrative for my life and the one I was forming for myself. In my daddy's car, it's you I really wanna drive, Prince sings in the title track, but you never go too far. I was feeling that same urge—that desperation to explore the limits—and my life seemed to be aligning with Prince lyrics. For a couple of months now, my ride, a prune-juice colored '74 Camaro I called the Badmobile, had been in and out of the shop with symptoms no trained mechanic could seem to remedy. So I'd been resigned to borrowing my father's vehicle. And though Dad's Ford Fairlane was the site of some of our most heated encounters, Yvette and I vowed to go only so far within its confines. Granted, there were those bench seats, front and back, which seemed an open invitation to all manner of vehicular amour. But Dad kept a pocket-sized New Testament in the glove compartment—out of sight, sure, but like the Holy Ghost, always present.

"Take Me With You"

It's hard to say exactly whose idea it was, whether it was Yvette's or mine, but eventually we began thinking of ourselves as Prince and Apollonia. The world was bathing in Purple Rain. We memorized every lyric of the album and line of dialogue from the movie. Then came a conscious attempt to act out the script in our daily lives. But instead of climbing aboard a purple motorcycle, we'd cruise over to the local park in the Badmobile, where we'd feed breadcrumbs to the ducks and pretend the murky pond was Lake Minnetonka. Inevitably I'd tell Yvette that, if our relationship were to go any further, she'd have to "pass the initiation," just like Apollonia had passed Prince's, by stripping to her skivvies and "purifying yourself in the waters of Lake Minnetonka." If she took the bait, she'd jump in, just as I halfheartedly hollered, "Wait— ". Then when she emerged from the water, retching and gasping for breath, I'd of course say, "That ain't Lake Minnetonka." Yvette, however, did not follow this part of the script. She had smaller breasts than Apollonia, but a bigger brain.

"Darling Nikki"

Prince closes Side 1 of Purple Rain with the tune that prompted Tipper Gore to kick start the PMRC and commence stickering album covers with warning labels. The story goes that, after overhearing her 11-year-old daughter listening to Prince sing about a "sex fiend" who spends her time masturbating with magazines in hotel lobbies, Tipper was moved to action. "Darling Nikki" topped the list of what she called the "Filthy Fifteen." But if she'd had the time, know-how, and inclination to play the end of the song backwards on a turntable, Tipper would have heard Prince uttering these words: Hello, how are you? I'm fine, ‘cause I know the Lord is coming soon. Only Prince could deliver one of the decade's most salacious tracks and finish it off with a reminder that the Rapture is on its way.

"Purple Rain"

Of course, like the 80s, like Prince's purple reign, like youth, Yvette and I came to an end. I was going away to college, and, well, I told her I thought we should see other people. She did not take the news well. What she took instead was a bottle of pills.

Her stepfather phoned me from the emergency room. "I'm the one calling," he said, "because her mother can't stand the thought of talking to you. She doesn't want you to come here—but Yvette insists on seeing you. Her mother can't tell her no right now."

On the ride to the hospital I had ample time to consider whether I was culpable for the fact that Yvette had decided to ingest a medicine cabinet in protest against my desire to exit our relationship. Instead of pondering the cause-and-effect, though, I played the song "Purple Rain." It seemed like the thing to do. I felt like I owed Yvette eight minutes and forty-five seconds of my complete and undivided attention.

When I arrived at the ER, I found her sitting upright on a cot and holding a pan of puke in her lap. Her lips were black with the charcoal the nurses had been making her drink to induce vomiting.

I don't recall much else from that night except this: I took the long way home from the hospital, out on I-166 where the streetlights disappear and the road is Bible black. I rolled down the windows and cranked up the volume—and rewound the tape, over and over. I never meant to cause you any sorrow/ I never meant to cause you any pain/ I only wanted to one time seeing you laughing/ In the purple rain.

It was true. I hadn't wanted to hurt Yvette. I'd only wanted her to have some fun.

"The Cross"

Near the end of 1987's Sign of the Times, Prince makes perhaps his most straightforward and evangelical declaration of Christian faith to date. He sings the same set of verses twice over, once accompanied by an acoustic guitar, and again against a backdrop of raucous rock guitar and a banging drum. It's a simple, plaintive song, with a singular plea: Don't cry, he is coming/Don't die without knowing…the cross.

"Anna Stesia"

Let's start with that album cover. Wal-Mart refused to stock 1988's Lovesexy. Other outlets wrapped it in black paper. A completely nude Prince reclines against a giant orchid, his strategically raised thigh covering his unmentionables. As if all this weren't enough, there's a flower stamen nearby. It's not exactly subtle symbolism. It's a sexual image, sure, but listen: it's also a spiritual one. On this record our boy is reborn. From its opening testimony of personal salvation to its closing roll of baptismal waters, the album contains as much evangelical zeal as any pulpit sermon I heard in my youth. In its thematic centerpiece, "Anna Stesia," Prince attributes his failure to love a woman properly to his failure to love God wholly. The turning point comes when he sings, Save me, Jesus, I've been a fool/How could I forget that you are the rule?/You are my god, I am your child/From now on for you I shall be wild. Then in a climactic, sing-along chorus, Preacher Prince proclaims, Love is God/God is Love/Girls and boys, love God above. This simple declaration is Biblical, of course, and nothing new. But when Prince utters the words they seem to be striking him as nothing short of an epiphany.

Eventually I would marry a woman with a Jewish father, a Catholic mother, and her own religious identity to reconcile. Today we're raising our daughter Jewish, and she's preparing for her Bat Mitvah. Recently she asked me the inevitable: "Dad, what do you believe?"

How does one distill his personal theology into a few words?

I thought for a minute, then answered the only way that really makes sense to me nowadays: "Love is God, God is Love," I told her. "Girls and boys, love God above."

Mark Beaver and Suburban Gospel links:

Kirkus review

Publishers Weekly review

Michigan Quarterly Review interview with the author

also at Largehearted Boy:

Book Notes (2015 - ) (authors create music playlists for their book)

Book Notes (2012 - 2014) (authors create music playlists for their book)

Book Notes (2005 - 2011) (authors create music playlists for their book)

my 11 favorite Book Notes playlist essays

100 Online Sources for Free and Legal Music Downloads

Antiheroines (interviews with up and coming female comics artists)

Atomic Books Comics Preview (weekly comics highlights)

guest book reviews

Librairie Drawn & Quarterly Books of the Week (recommended new books, magazines, and comics)

musician/author interviews

Note Books (musicians discuss literature)

Short Cuts (writers pair a song with their short story or essay)

Shorties (daily music, literature, and pop culture links)

Soundtracked (composers and directors discuss their film's soundtracks)

weekly music release lists

Word Bookstores Books of the Week (weekly new book highlights)