« older | Main Largehearted Boy Page | newer »

April 7, 2016

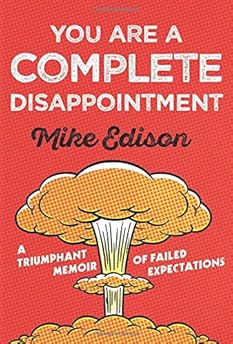

Excerpt: Mike Edison's Memoir You Are a Complete Disappointment

The following is from Mike Edison’s memoir, You Are a Complete Disappointment (out May 3rd from Sterling Publishing). Mike Edison is the former editor and publisher of High Times magazine. His books include the memoir I Have Fun Everywhere I Go and the sprawling social history of sex on the newsstand, Dirty! Dirty! Dirty!. More recently he collaborated with Joe Bastianich on his New York Times bestselling memoir, Restaurant Man. Edison has worked as a foreign correspondent for Hustler and was a high-paid gun-for-hire of the legendary Penthouse letters. He has contributed to numerous magazines and websites, including Huffington Post, the Daily Beast, the New York Observer, Spin, Interview, and New York Press, for which he covered classical music and professional wrestling. In addition, he is an internationally known musician and ferociously dedicated storyteller who can be heard every Sunday on his show Arts & Seizures on the Heritage Radio Network. Edison lives and works in Brooklyn.

I was about seven years old the first time I tried Atomic FireBalls, the hard, super-spicy cinnamon candies that burn hot and sweet and make your mouth all red. I think I was just attracted to the packaging—there was a mushroom cloud on the box that spoke to their genuine atomic power—and decided to give them a go, rather than buy my usual ZotZ.

ZotZ, if you recall, were hard candies filled with a sour, fizzy powder. Bicarbonate of crap, I think it was called, and when you got to the center (meaning when you broke it in half with one good crunch), your entire mouth was filled with foamy white stuff, which (if you had some good technique) you could make trickle out over your lips as if you were having a seizure. It was kind of gross and kind of cool, and when we were just a little bit older we definitely realized that it had some odd sexual overtones, like the bubble gum filled with liquid that squirted into your mouth when you bit down on it.

Atomic FireBalls were nothing short of a gut punch—the first “hot” food that I had ever tried—and they thrust the rest of my flavorless suburban life into the shadows. Everything else sucked. Atomic FireBalls ruled. They would be my new religion.

“You’ve got to try one of these!” I insisted to my dad, evangelical in my exuberance that this was the single greatest thing that had ever happened to me. “They’re fantastic!”

“No, I am not going to try one of those, whatever they are,” he told me, showing his disapproval with what I would come to know as a well-practiced look of utter disgust. Then he made a big show of offering me his candy of choice, Necco wafers, which were quarter-sized disks that tasted like old waxed paper and grout that I pretended to like because I wanted to have something I could share with my father. I didn’t want to hurt his feelings by spitting the foul thing out on the floor, which was my first instinct, and I later found out that tasting as if they had been left on the shelf since the Civil War was actually their biggest selling point—it took a special kind of rank, gastronomic nostalgia to eat them.

The Atomic FireBall was ground zero for the Taste Wars, and from there a lifetime’s worth of absurd Father v. Son ad hominem challenges began. Pretty much right up until he died, every time I tried something new and liked it, whether it was a breakfast cereal or a new pizza topping—if I had the audacity to try and share it—I was rebuffed and told to “grow up.”

It’s ridiculous, I know, but when I was a child, I was constantly told to “just grow up already.” Seven years old and already I was being indicted for the crime of “immaturity,” which Ambrose Bierce might have described as “the word old people use to put down younger people who have more fun than they do,” never mind the absurdity of measuring a second-grader’s choices in candy, cartoons, and breakfast cereal against that of an Ivy-educated suburban father of three, or the insanity of pushing his Eisenhower-era tastes onto the palate of a kid who had just entered the Brave New World of Atomic FireBalls—which, I can tell you now, was most definitely a gateway to harder stuff (Tabasco sauce, jalapeños, tequila, LSD, etc).

Later, I came to realize that my dad’s childhood had been deflated by similarly unimaginative parents. He was born of adults who somehow skipped or just repressed the ecstasy and horrors and general confusion of being young, adults who were incapable of experiencing the travails—joyful, playful, sad, hurt, whatever—of their own children. His folks were society stiffs who would never get down on the floor and crawl around on the carpet with their toddlers. They weren’t huggers or listeners, and they certainly didn’t know how to be silly, or play games, or have any sort of fun that strayed from their uptight parochial formulary, and it stuck with him when he had kids of his own.

Throughout my childhood he made fun of me all the time for what I watched on television: popular sitcoms like Happy Days and Good Times, which the kids in school liked to talk about at lunchtime, seeing who could do the best imitations of the Fonz or Jimmy “Dyn-O-Mite” Walker; Chiller Theatre, which showed mostly B horror films like The Brain That Wouldn’t Die, Attack of the Crab Monsters, and Psychomania (a British biker-horror masterpiece about a motorcycle gang that came back from the dead—they were actually buried on their choppers and rode them straight out of the grave, which is every bit as awesome as it sounds); Creature Features, which favored old-school Universal Studios monster movies (The Mummy was my favorite) and Christopher Lee’s slightly risqué Dracula flicks; and, of course, Championship Wrestling, which came on at ten o’clock on Saturday mornings, followed by the roller derby that I loved but could not for the life of me ever figure out how they kept score.

He took special glee in mocking me for watching the wrestling—It’s fake! It’s not real! Grow up! How dumb can you be? But truthfully, even at seven years old, I knew in my heart of hearts it wasn’t legit. How could it be? We all had heard the rumors that Chief Jay Strongbow was really an Italian guy from the Bronx, and even a blind man could see the pulled punches from a mile away. But then, like now, it didn’t matter. It was a world unconfined by the laws and rules the rest of us had to obey. In wrestling there was justice, and there was freedom. Wrestling was all about the power of imagination.

Then, and as ever, I championed the bad guys, and especially their preposterous manager-cum-mouthpieces, for whom it was a Golden Era, led by a triumvirate of lunatics: “Captain Lou” Albano, who spat when he talked and inexplicably had rubber bands attached to his face, like some sort of escaped mental patient; the Grand Wizard of Wrestling, a shriveled Jewish man who wore hideous madras jackets, sparkly turbans, and wrap-around shades and who claimed to be the smartest man in the world; and “Classy” Freddie Blassie, the self-proclaimed “King of Men” who even had his own hilarious song, “Pencil Neck Geek.” They were larger than life. They oozed a certain retarded charisma that I still find irresistible.

Anyway, when my dad told me to “grow up” at age seven, I knew even then it was ridiculous. I probably rolled my eyes and went back to watching Kung Fu Theater and stuffing my mouth with ZotZ just to see how much foam I could spew. Even then I was never really one for “growing up,” such as it was. I was always more about evolving.

Our last great shared moment—my father and I—was July 20, 1969, when he woke me up to watch the first man land on the moon. I remember it clear as a bell, sitting on the edge of my parents’ bed, with its soft, blue summer cotton sheets, staring at the black-and-white Philco television set. The blurry image moved haltingly across the screen, and the crackling audio percolated from the tiny speaker, the first transmission from another world.

I was in love with the space program, agape with the gauzy optimism of exploration, gaga for the gadgetry and gee-whiz of NASA. I still reminisce about the blue NASA jumpsuit I had my picture taken in when I was eight, and about how I wanted to be a space captain and have sex with Barbarella and all of her friends when I was sixteen. After watching the first man land on the moon, my mind was racing with possibilities, because even at the cusp of my fifth birthday, I was a man with a vision. Well, that’s my version of it. Others might say I was a hopeless dreamer.

Looking back, I have come to realize the fundamental difference between how I saw the first moon landing and how my father saw it: He saw expensive hardware and American exceptionalism. I saw adventure. I saw rockets and stars. He wanted to meet the astronauts and ask them what it was like to walk on the moon. I wanted to go there and find out for myself.

From You Are a Complete Disappointment: A Triumphant Memoir of Failed Expectations. Used with permission of Sterling Publishing. Copyright © 2016 by Mike Edison.