« older | Main Largehearted Boy Page | newer »

August 22, 2016

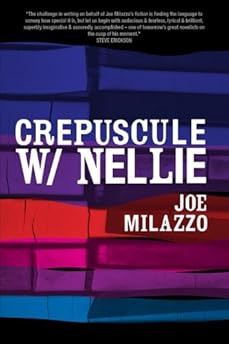

Book Notes - Joe Milazzo "Crepuscule W/Nellie"

In the Book Notes series, authors create and discuss a music playlist that relates in some way to their recently published book.

Previous contributors include Bret Easton Ellis, Kate Christensen, Lauren Groff, T.C. Boyle, Dana Spiotta, Amy Bloom, Aimee Bender, Jesmyn Ward, Heidi Julavits, Hari Kunzru, and many others.

Joe Milazzo's novel Crepuscule W/Nellie is an inventive, challenging, and rewarding book centering on the life of jazz legend Thelonious Monk.

Steve Erickson wrote of the book:

"The challenge in writing on behalf of Joe Milazzo's fiction is finding the language to convey how special it is, but let us begin with audacious and fearless, lyrical and brilliant, superbly imaginative and assuredly accomplished--one of tomorrow's great novelists on the cusp of his moment."

In his own words, here is Joe Milazzo's Book Notes music playlist for his novel Crepuscule W/Nellie:

If any reader wants to call Crepuscule W/Nellie "Thelonious Monk fan fiction," I'm not going to argue with them, and who would I be to do so anyway? The novel's plot may be recondite, its language elaborate, but its premise is actually quite simple and even familiar. What if Thelonious Monk's music were his autobiography? That is, what if the music were a perfectly accurate representation of the artist's life? No sublimation, no distinction between background and foreground, no need for interpretation or translation. Anyone who has ever considered themselves a fan knows the deliciousness and terror of obsession's exclusivity. The expectation (hope?) we might reach through the art and touch its creator both inflames and humiliates us. In some ways, the fulcrum of our fandom is just this impossible intimacy, so palpable and yet so incapable of ever being consummated. Of course, consummation isn't what we want. Unless the prolongation of our desires be some form of resolution. (And perhaps this is why Crepuscule W/ Nellie is as long a book as it is, and this helps to explain why my laboring over it lasted the years that it did.)

Nevertheless, and contrary to the amount of Monk's music that appears in this playlist, Crepuscule W/Nellie is not really a novel about Thelonious Monk. It's not even a novel about Monk's largely, historically silent wife, Nellie. Crepuscule W/ Nellie is a novel about listening. And the novel's listening is not just trained on jazz, even though it is partly a consequence of a deliberate decision I made in college to make myself over as a jazz listener. As an artistic work, Crepuscule W/ Nellie could not exist without the listening I learned by attending to the voices and stories I heard growing up. Crepuscule W/ Nellie's own characters struggle against the positions that listening imposes upon them. Nellie, The Baroness, John, Monk himself: each of them has to come to terms with the truth that, just as they think they are pulling off a performance, they realize that they are in fact the audience to a greater performance, one whose ongoing existence they had never before suspected.

That experience ultimately mirrors my own authorial experience with respect to Crepuscule W/ Nellie. I am as much the book's witness as I am its composer; the book came to be only once I accepted that it was a phenomenon happening to me, to which I would have to improvise my own response. This playlist is another expression of that response. This playlist is part index—"here's what I was listening to while I wrote this novel")—part encyclopedia—"if I could reconstruct knowledge of who I was when I was writing this book, here's a soundtrack I'd hear playing over that footage"—and part critical essay—"here's the music I'd most want readers to have heard in order to appreciate the novel and its references." More importantly, this playlist is intended to be entirely a gift. I invite you to activate this listening on your own terms, and to follow your listening's associations wherever (and to whomever) they lead.

1) "Crepuscule with Nellie," Thelonious Monk. From Monk's Music (Riverside, 1957). Thelonious Monk (piano), with Ray Copeland (trumpet), Gigi Gryce (alto sax), Coleman Hawkins (tenor sax), John Coltrane (tenor sax), Wilbur Ware (bass), Art Blakey (drums)

Some readers have asked me: "Why Crepuscule W/ Nellie and not Crepuscule with Nellie?" The short answer is that I don't really know, except that I think I must have first seen the title to this Thelonious Monk composition spelled that way. I.e., that I've always known Nellie Monk, Thelonious's wife and the subject of this composition (one which was always performed by Monk as a composition, without any improvisation) in this guise. The longer and more true answer is that, while the novel contains a scene which proposes to explain how "Crepuscule with Nellie"'s unconventional reconciliation of the discordant and the lyrical (or: the devil's blues and the angels' hymning) came to be, the composition the novel's prose describes is not really "Crepuscule with Nellie." (The true story of this song is far more dramatic anyway.) Maybe that song is a proto-"Crepuscule with Nellie," or a "Crepuscule with Nellie" that, while it sounds very reminiscent of the one we can listen to in our own world, exists only in the novel's parallel universe. "Crepuscule with Nellie" is Nellie as Monk knew and loved her. "Crepuscule W/ Nellie" is the Nellie Monk my imagination introduced to me. I wouldn't know that Nellie without "Crepuscule with Nellie," but the distinction is crucial—even though I am still puzzling out exactly what that distinction means.

2) "Pannonica," Thelonious Monk. From Thelonious Alone in San Francisco (Riverside, 1959). Thelonious Monk (solo piano)

"Crepuscule with Nellie" is a bit like a monochrome kaleidoscope: its shapes play and short and refuse to settle, but they share a common palette, and there's comfort in that. "Pannonica," which Monk wrote for his patron and friend (and eventual housemate) the Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter is like a rainbow fashioned out of iron. So many moods, form the rapturous to the melancholy (check that turnaround), are packed into a few bars, but their rise and fall is more… predictable? First hearing this particular performance, I thought how much more Monk sounded like a stride piano player here (he also loved to make Art Tatum-esque runs when playing this song, not something you are going to hear him do much of elsewhere in his discography); that I still couldn't picture the woman who was the ostensible subject here; and wondering why this composition was suffused with so much more romantic tenderness than "Crepuscule With Nellie." Of course, I hear the aching in both songs much differently now that I've been married for nearly a decade myself. As I continued to work on Crepuscule W/ Nellie, this song, perhaps even more so than Nellie's, came to represent for me a question that drove both the book's plot and the meta-narrative of my own imaginative diligence: is it possible for any masculine attempt to honor the feminine not to fail? And so this composition is also apparently auditioned for its subject in my novel, but, as with Crepuscule W/ Nellie, whether or not it is actually heard is open to question.

3) "Cement Mixer (Put-Ti-Put-Ti)," Slim Gaillard. First recorded in 1946 for Cadet Records. Slim Gaillard (piano and vocal), Tiny Brown (bass and vocal), Zutty Singleton (drums)

Either I am or "Nellie Monk" (the character) is guilty of a terrible anachronism with respect to this song. Nellie remembers it as being popular in the 30's, predating even her acquaintance with a pre-famous Thelonious Monk. She also associates it with a vanished Harlem, when, in fact, Slim Gaillard was very much a Hollywood personality. Now, it is entirely possible that Nellie is completely fluent in "vout" (Gaillard's invented nonsense language), and that the choruses she takes on both this song and "The Flat-Foot Floogie (with a Floy Floy)" constitute something of an admission (if not a confession) as to how much her own story is being fabricated on the fly. I somehow can't imagine Nellie's long monologue midway through the novel without Gaillard's original hipster example. Certainly, I believe Gaillard as an exemplar of stream of consciousness narration deserves as much approbation as Joyce, Faulkner, or Woolf. I should also point out that "cement mixer" is also a slang term that, in the 1930s, carried a double meaning: it referred to a sexually explicit pelvic dance-move (we call it grinding) and was also basically synonymous with "hoofer"—a hopelessly bad but helplessly enthusiastic dancer.

4) "Skippy," Thelonious Monk. Genius of Modern Music Volume 2 (Blue Note). Originally recorded in 1952. Thelonious Monk (piano), Kenny Dorham (trumpet), Lou Donaldson (alto sax), Lucky Thompson (tenor sax), Nelson Boyd (bass), Max Roach (drums)

Was Thelonious Monk mentally ill? Did he suffer from bipolar disorder, was he schizophrenic, or were some of his more odd behaviors the result of chemical abuse? The state of Monk's mind is a problematic area of inquiry for any number of reasons. There's simple prurience for one. Most pertinently, I think the question elides issues of race and what it must have been like to be an African-American artist and public figure in mid-20th Century American life. Monk's actual biography is full of incidents, many of them relating to the color of his skin, that would leave anyone with symptoms of PTSD. From the loss of his cabaret card to police beatings to the reception his music received in certain quarters, Monk had plenty of reasons to be "mad." My solution, if I can call it that, to the problem of how to portray Monk in this novel was never to portray him except from the perspective of others. In effect, to turn the gaze of his own music back on him through the women at whom he gazed in writing "Crepuscule With Nellie" and "Pannonica." Monk is something of a blank in the novel, constantly being filled in, or he is the hole at the center of the record. But there are certainly moments in the book when he demonstrates that his eccentricity may be both more and less than that. As one reader has observed, "the book is full of clever people working on some con, and Monk presides above it all as the King of the Tricksters." This particular composition feels like an expression of that side of the man's character. "Brilliant Corners" has the reputation of being Monk's most difficult to play composition (and the number of takes it took to record it nearly cost alto saxophone payer Ernie Henry his sanity), but the earlier "Skippy" is true earworm sadism. An Escher-esque, double-backing theme that doesn't exactly announce itself as a theme, "Skippy" announces itself with a piano introduction that "only Monk could play." The ensemble enters only to play a brief fanfare that, if we respect the head-solos-head vocabulary of most bebop performances, must be the actual composition. But the recapitulation reveals that Monk's opening improvisation was in fact the composition itself, and the horn players somehow have to reproduce Monk's line. It's like a musical game of Horse. And the Monk of Crepuscule W/ Nellie is rather proud of his abilities on the basketball court.

5) "Tenor Madness," Sonny Rollins and John Coltrane. From Tenor Madness (Prestige, 1956). Sonny Rollins, John Coltrane (tenor sax), Red Garland (piano), Paul Chambers (bass), Philly Joe Jones (drums)

The saxophone-playing John in Crepuscule W/ Nellie may or may not be John Coltrane. "John" is a very common name after all. And I chose that name as much for the specific figures it may evoke as for the colloquial meanings that have attached themselves to it and whose play I wanted to preserve. But if this John is a nascent Coltrane, then this track, which features a head-to-head by the two young saxophonists who woodshedded most productively with Monk in the 1950s, is one to which the montage of John's surreal "cutting contest" in the novel might be click-tracked.

6) "Stickball (I Mean You)," Johnny Griffin & Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis. From Lookin' at Monk (Jazzland, 1961). Johnny Griffin, Eddie "Lockjaw" Davis (tenor sax), Junior Mance (piano), Larry Gales (bass), Ben Riley (drums)

But if John isn't Coltrane, maybe he is Johnny Griffin, the tenor player who replaced Coltrane in Monk's working quartet that held down a regular gig at New York's Five Spot in the late 1950s. Aficionado opinion on Griffin as an interpreter of Monk's music seems a bit divided. Some find his occasional forays into R&B-inspired Tarzan yelps and chest-thumps too theatrical. Others claim that Griffin is the only musician to have played with Monk who "never learned anything from him." And there's the critical notion: that one did not just play with Monk; one "discipled" with him. Crepuscule W/ Nellie is a novel about two women, but, when it does turn its attention to men, it's very much concerned with the ways in which men frequently attempt to take care of each other by erecting certain power structures in which that care, being bound up as it with a certain dynamic of respect, cannot be mutual. Myself, I like Griffin's energy and find him to be a sneakily cerebral player. The poetically nicknamed Lockjaw, however, was the truly sui generis player in this band, and his exploits merit a novel of their own.

7) "Short Life of Barbara Monk," Ran Blake. From Short Life of Barbara Monk (Soul Note, 1986). Ran Blake (piano), Ricky Ford (tenor sax), Ed Felson (bass), Jon Hazilla (drums)

No question about it: Crepuscule W/ Nellie is a melodrama. I myself have no direct experience of the 1950s, and so could only fictionalize them through other fictions. While I relied upon literary representations of that decade (Ellison, Gaddis, Clellon Holmes, to name but a few), I also borrowed extensively from movies. Alexander MacKendrick's Sweet Smell of Success was one, and so were the "women's pictures" made by Douglas Sirk. This lovely, vaguely unsettling "Crepuscule with Nellie"-like (note the discrete sections spliced together) composition was penned by Ran Blake, one of the few living musicians to have actually known and worked with Thelonious Monk. It's dedicated to Monk's daughter Barbara (herself named after Monk's own mother), who died at the age of 31. Barbara, whose nickname was Boo-Boo, appears only briefly in Crepuscule W/ Nellie. Or is it that Boo-Boo materializes, a ghost who somehow and somewhere else exists in the flesh? I was definitely inspired by Blake's incorporation of Bernard Herrmann-like melodies and cadences here. Again, Crepuscule W/ Nellie is a melodrama, which is to say that Crepuscule W/ Nellie's characters are tormented equally by the clichés of the tear-jerker and the thriller. Especially as the novel exposes her relationship with her daughter, Nellie knows this too.

8) "Yesterdays," Dizzy Reece. From Soundin' Off (Blue Note, 1960). Dizzy Reece (trumpet), Walter Bishop Jr. (piano), Doug Watkins (bass), Art Taylor (drums)

An appropriately brooding version of this standard that captures as well as any example of hard bop the confusions and frustrations smoldering beneath the implacable surfaces of "the cool." Trumpeter Reece, to my knowledge, never actually played with Monk, though he is the author of a fine Monk tribute ("A Variation on Monk," from the Blue Note LP Star Bright). But I want to spotlight this performance as much for its accompanying visuals as for the music itself. The character of Nica/the Baroness in the novel is rather fixated on her record collection, and, on several occasions, we witness her musing over the syntax and semiotics of what have become, in the intervening years, era-defining and much imitated designs (thanks, Reid Miles and Frank Woolf). Obscure as this record is, something about the cover just feels quintessentially jazz as whiteness knows it. Jazz as "jazz," or "jazz" as the Coen Brothers might mock it and as it still infect my white imagination: a style naive in its calculatedness. The lone horn player blowing pensive, sweater-vested, poised with his horn against the black of idealized night. In reality, the encompassing bleak is only a warm, dimmed studio, and the mood is all in the cropping.

9) "Smoke Gets in Your Eyes," Thelonious Monk. From Monk (Prestige, 1954). Thelonious Monk (piano), Frank Foster (tenor sax), Ray Copeland (trumpet), Curly Russell (bass), Art Blakey (drums)

One of Monk's most famous/infamous treatments of a popular song. Some have described this arrangement as tantamount to punk rock, hearing in Monk's reharmonization of the Harbach/Kern chestnut a defacement of lazy, lowest common denominator Tin Pan Alley sentiment. This version has its comic moments, sure, but I can hear the Buster Keaton in it, too. (How he hammers his way through the bridge, or stone-faces his way through the burning hearts and tears-I'll-pretend-aren't-tears of the verses.) The real cruelty here, of course, is all in the emotional reductiveness of the original. If this version feels distorted, it's because the actual emotions Monk has to express are incommensurate with the medium he's chosen. So why choose that medium at all? We might as well ask why art requires the material at all. The relationship between art, medium, and material is one of those obvious mysteries: we accept that they must interact this way, we carry on, but the longer we live with the assumptions that ensure art's working order, the more they begin to dissolve and transmogrify and force themselves upon our considerations. Nellie quotes the lyrics of "Smoke Gets in Your Eyes" to herself on more than one occasion in the novel. Even subjected to Monk's interventions, I believe it's a tune she recognizes more easily than she'd like.

10) "Pomp," Chet Baker. From Chet in Paris, Volume 1 (Barclay/Emarcy, 1954). Chet Baker (trumpet), Richard Twardzik (piano), Jimmy Bond (bass), Peter Littman (drums). Composed by Bob Zieff

If any character in Crepuscule W/ Nellie requires a leitmotif, that character is Frank, The Baroness's erstwhile valet. But any leitmotif risks giving too much away. Other options I entertained: Grachan Moncur III's "Frankenstein" (too sinister); Andrew Hill's "Subterfuge" (too telegraph-y); June Christy's 1954, Pete Rugolo-arranged rendition of the Kurt Weill-Langston Hughes collaboration "Lonely House" (too sympathetic); Babs Gonzales's "Weird Lullaby" (too Nellie). Nevertheless, whenever Frank isn't imminent in the novel, he is pervasive. As I look back on the process by which Frank emerged from the props I collected for the purposes of staging Crepuscule W/ Nellie and declared himself to be among the story's actors, I realized that he was the book's most Pynchonian character. Frank is a primary vector of paranoia in the book, but the paranoia that drives him and whips him up is far pettier than the justifiable paranoia that paralyzes many of the novel's other characters. Something about the way Chet Baker's trumpet has to reach to execute Bob Zieff's theme; something about the way Richard Twardzik's piano solo (lightly Brubeckian, vaguely Tristano-like) can't entirely suppress its sarcasm; something about the way the band hits those descending chords that follow the composition's initial phrase; something about the way the whole tune moves sideways rather than progresses; something about the way the solos really bring out the work song (if not field holler) in the tune's changes… all of these aspects of this performance speak to the horrible and ridiculous things of which Frank proves himself capable.

11) "Love, Gloom, Cash, Love," Herbie Nichols. From Love, Gloom, Cash, Love (Bethlehem, 1957). Herbie Nichols (piano), George Duvivier (bass), Dannie Richmond (drums)

Before there was Crepuscule W/ Nellie, there was another book, a collection of short stories and novellas about various figures in jazz history. In addition to a "Monk story," this manuscript included fictions about Ornette Coleman, Art Pepper, Charles Mingus, Sonny Rollins, the aforementioned Andrew Hill, the soon-to-be-mentioned Freddie Redd, and a few others. The working title for this manuscript was, at one time, Come Sunday. Until I learned that Bradford Morrow of Conjunctions had already quoted Duke Ellington in titling his own debut novel. I ultimately settled on Love, Gloom, Cash, Love, a brilliant summation of the jazz life as observed by Herbie Nichols, one of the music's most poetic figures. (I also liked that "Love, Gloom, Cash, Love" wasn't a ballad, or an up-tempo blowing vehicle, but an original in waltz time.) Nichols was one of the very first musicians to analyze Thelonious Monk's music, and his talents should have earned him greater rewards during his brief lifetime. Instead, Nichols has had to settle for being a cult figure within what's already a shrinking subculture, and for being not even the mayor but the patron saint of jazz's Palookaville. Love, Gloom, Cash, Love ended being an unsalvageable project save for a few pages of that original "Monk story." I do miss that title, though, and the wonky grace of its tautologies.

12) "Picasso," Coleman Hawkins. From The Jazz Scene (Clef/Mercury, 1949). Coleman Hawkins (tenor saxophone)

Coleman Hawkins, aka "The Bean" (though I forget the origins of that nickname and refuse to Google them right now), was another of Monk's first musical supporters. In fact, Monk's very first commercial recording was made under Hawkins's leadership. In the novel, Bean offers a different take on Monk's musical origins. But my favorite Bean scenes to write come near the novel's conclusion: when he trades his tenor saxophone for John's (stolen) cowboy hat, and as he's making his way to Europe. Unaccompanied saxophone improvisations such as this one were practically unheard-of in 1948. Maybe, on first listen, it sounds as if Hawkins is "just rehearsing" here. But, in jazz, what seems casual hardly ever is. Bean is one of the older characters in Crepuscule W/ Nellie, but the novel ends with the suggestion that his future is less murky than the futures facing Monk, John, Nellie, the Baroness, et al. Likewise, in many ways, this performance is looking ahead to post-Monk developments in jazz.

13) "Low Tide (Bird's View) (Alternate Take)," Elmo Hope. From The Final Sessions, Volume 1. (Inner City / Specialty Records / Original Jazz Classics, 1966). Elmo Hope (piano), John Ore (bass), Philly Joe Jones (drums)

John Litweiler, one of the best writers to ever take up the subject of jazz, has this to say about the modern jazz of the 1940s:

The purest manifestation of bop—the music of Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Fats Navarro, Bud Powell—was a music of extremes. There were the extremes of bop's harmony, its mixtures of consonance and dissonance, its substituted harmonic structures. More extreme were bop's rhythms: the slippery accents among even tiny note values; the broken lines of eighth notes; the shock of sudden double-time runs. The fast tempos, the speed of the lines, the electrocuted leaping in the high, middle, and low ranges of the musical instruments required a coordination of nerve, muscle, and intellect that pressed human agility and creativity towards their outer limits. Bop was an exhilarated adventure; in Gillespie's dizzying trumpet heights, in Powell's hallucinated piano excitement, a deadly fall to earth is ever possible." (The Freedom Principle: Jazz After 1958, 14.)

Did Monk himself actually play bop as Parker and his "worthy constituents" did? This remains an open question. Regardless, Monk, whose personal life was more grounded than that of many jazz musicians, and whose abstractions never lacked for earthiness, will forever be identified with bop as its putative "High Priest." So we may have to listen elsewhere for what made bop bop. For me, few performances capture Litweiler's risks of bop as well as this one by pianist and composer Elmo Hope, made more than 20 years after the bop revolution. Somewhat dismissed during his career as a Bud Powell imitator, his sensibilities were more than a little Monkian. Dedicate just one listen to concentrating on Hope's left hand here, paying as little mind as you can to the fireworks spectacle that is his right hand. Finally, I also wanted to include an alternate take here, as Crepuscule W/ Nellie is not arranged in chapters but instead follows the conventions of the jazz discography, which prioritizes chronological order over any kind of narrative logic.

14) "Nica Steps Out," Freddie Redd. From San Francisco Suite (Riverside, 1957). Freddie Redd (piano), George Tucker (bass), Al Dreares (drums)

There is no shortage of Nica songs. Such was the power of the Baroness's genuine affection for New York's jazz community. But Nica was was also glamorous, notorious, wealthy, and white. Nica was, by all accounts, a personality too big for any novel. Of course she inspired: "Nica's Tempo" by Gigi Gryce; "Nica's Dream" by Horace Silver; "Blues for Nica" by Kenny Drew; even Sonny Rollins's famous version of "Poor Butterfly" can be heard as being in homage to a woman named by an amateur lepidopterist. Pianist and composer Redd gives the showgirls plenty of opportunities to kick up their heels during these four-and-a-half minutes. Whether Crepuscule W/ Nellie's Nica belongs in this chorus line or whether "her place" aligns with serving as hostess for the after-show party I leave to the listener's (and reader's) imagination.

Hidden bonus track: Jim Sangrey & Summusic's "Hey Joe (Where You Goin' with That Book in Your Hand)"

Joe Milazzo and Crepuscule W/Nellie links:

The Collagist review

Kirkus review

Necessary Fiction review

2paragraphs interview with the author

Don't Do It interview with the author

Entropy interview with the author

also at Largehearted Boy:

Support the Largehearted Boy website

Book Notes (2015 - ) (authors create music playlists for their book)

Book Notes (2012 - 2014) (authors create music playlists for their book)

Book Notes (2005 - 2011) (authors create music playlists for their book)

my 11 favorite Book Notes playlist essays

100 Online Sources for Free and Legal Music Downloads

Antiheroines (interviews with up and coming female comics artists)

Atomic Books Comics Preview (weekly comics highlights)

guest book reviews

Librairie Drawn & Quarterly Books of the Week (recommended new books, magazines, and comics)

musician/author interviews

Note Books (musicians discuss literature)

Short Cuts (writers pair a song with their short story or essay)

Shorties (daily music, literature, and pop culture links)

Soundtracked (composers and directors discuss their film's soundtracks)

weekly music release lists

Word Bookstores Books of the Week (weekly new book highlights)