« older | Main Largehearted Boy Page | newer »

March 7, 2018

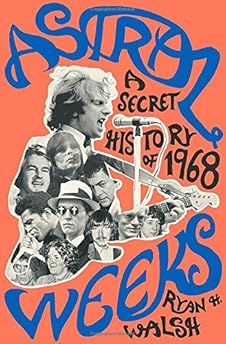

Book Notes - Ryan H. Walsh "Astral Weeks"

In the Book Notes series, authors create and discuss a music playlist that relates in some way to their recently published book.

Previous contributors include Jesmyn Ward, Bret Easton Ellis, Celeste Ng, Lauren Groff, T.C. Boyle, Dana Spiotta, Amy Bloom, Aimee Bender, Heidi Julavits, Hari Kunzru, and many others.

Ryan H. Walsh's fascinating Astral Weeks is a spirited history of the recording of the Van Morrison album of the same name and late-'60s Boston.

Rolling Stone wrote of the book:

"In 1968, Van Morrison was a rock & roll refugee, an Irish blues poet on the run after a bitter fling with pop stardom. Down and out in Boston, he wrote one of rock’s most beloved masterworks, Astral Weeks—then blew town. In this fantastic chronicle, Ryan Walsh unearths the time and place behind the music."

In his own words, here is Ryan H. Walsh's Book Notes music playlist for his book Astral Weeks:

“Sister Ray” (Live in Boston, 1968) – The Velvet Underground

This recording was captured in Boston in 1968, which is the precise time and place my debut book, Astral Weeks: A Secret History of 1968, is concerned with. After getting their start as a New York City art band associated with Andy Warhol, the Velvet Underground began to starve NYC of live shows and, instead, perform constantly in Boston—43 times between 1967 and 1970, in fact. Musician/critic Peter Laughner would later describe this time in VU's existence as being “sequestered in Boston's student ghetto.” On a typical evening in the backstage room of their local club of choice—The Boston Tea Party—Lou Reed held court talking over occult rituals with the club's janitor while Sterling Morrison sat in the corner teaching a teenage Jonathan Richman how to play guitar. This is “Sister Ray,” the seventeen minute closer of White Light / White Heat (that's the band standing in front of the Tea Party on the back cover of that LP btw) which was a set-list staple and could stretch out to a twenty-five minute feedback-jam during concerts. Richman would later comment how VU fill would fill the Tea Party room with all kinds of “ghost tones”— wild sounds you whose on-stage origin you could not locate. Listen for the ghost tones all over this recording. Tea Party club manager Steve Nelson spoke about how the audience could often be surprised by when VU would abruptly cut “Sister Ray.” The band would suddenly end the song and you'd see the crowd in the middle of a dancey sway try to catch themselves and begin applauding.

“Astral Plane” - Jonathan Richman

Natick, MA native Jonathan Richman's life would be forever altered by his fandom and subsequent friendship with the Velvet Underground—the band “made me a musician” he said—but discussions of the occult with Lou Reed at the Boston Tea Party must be accounted for as well. Reed would later characterize his passing of Alice Bailey's A Treatise on White Magic to Richman as a “big mistake.” In the book I attempt to trace this influence upon Richman's first batch of songs with The Modern Lovers. “Astral Plane” sticks out as a sore thumb in a collection of tunes about girl troubles and a love of all things New England. Richman would dial up Modern Lover Ernie Brooks in the middle of the night inquiring about the ethics of his unconscious slumber-journeys crashing into his potential love life, “Ernie, I think I entered her dream. Do you think that’s right?” But Richman would also catch Van Morrison's local live shows around this time too, including a 1969 show where Morrison performed much of Astral Weeks live on Lansdowne Street. Hearing Morrison's Astral Weeks made Richman “sob and sob. I was twenty. Stormy and beautiful.” Richman was also one of the early figures to try and shine a spotlight on the album's Massachusetts connections: “A lot of these songs were written in Cambridge...I listen to that record a lot and I think Boston, Cambridge again.” Somewhere between Lou Reed and Van Morrison, Richman's “Astral Plane” was born.

Van Morrison is one of two main figures that carry this book's story along, the other being a banjo/harmonica player named Mel Lyman, a gaunt, outspoken man who claimed he was God from the pages of an underground newspaper named Avatar. When Lyman created the Fort Hill Community commune in Roxbury, MA in late 1966, one of the earliest claims of the group's intentions were to create “the most beautiful music the world has ever known.” The book chronicles how far afield the FHC strayed from this goal, but also stops to point out how when they did actually focus on music the results were often beautiful. Jim Kweskin's 1972 America album was produced by Lyman using a pseudonym, Richard Herbruck (long story). This was Kweskin's first musical output since disbanding his famous Jug Band to follow Lyman and move to Fort Hill in 1968. On America, the jubilant, goofy sound of Kweskin's earlier releases is gone, replaced by a stark acoustic take on Americana, and it's pretty darn great. The album's 1971 release would quickly be overshadowed by Rolling Stone's two-issues expose of Lyman, Kweskin and the Fort Hill Community, which would cause all involved to retreat from the public eye completely. Kweskin wouldn't release any more music until 1977.

During an interview with one of Van Morrison's Boston musicians, he told me about one particular day in the studio in 1968 where he was temporarily replaced by a one armed drummer. The search for that one armed drummer lead to a man named Victor "Moulty" Molton who beat the skins for a successful local band known as The Barbarians. They famously appeared alongside The Rolling Stones and The Supremes in the 1964 T.A.M.I. Show concert film. “They were a good group, four wild-hair boys with an electric presence,” wrote The Boston Globe, “but the real drawing card was Moulty, the drummer with a hook where one of his hands should be.” Moulty had blown his hand off fooling with a firecracker as teenager, and his tale of overcoming this tragedy would provide the lyrical content of The Barbarian's 1966 song entitled “Moulty.” As it turns out, “Moulty” is a cash-in novelty single where the drummer delivers his tragic tale in a spoken word recitation as The Band (yes, The Band) backs him up musically. The rest of the Barbarian's wanted nothing to do with the song. Moulty was convicted for possession of marijuana shortly after and the band went kaput. Moulty's time as Morrison's drummer, apparently, only lasted one day at Ace Recording Studio in Boston. Moulty says Morrison asked him to join the band and declined; Bebo, Morrison's regular Boston drummer, says Moulty played too hard for Van's tastes.

“People Get Ready” - The Mel Lyman Family

The Petrucci & Atwell recording studio—located at 330 Newbury Street, set inside a remodeled carriage house—would soon shut down and be replaced by Gunther Weil's Intermedia Studio (where Aerosmith would record "Dream On,") but in 1969, the Mel Lyman Family had made themselves a frequent presence on the premises. On July 20th, 1969, as three American astronauts touched down on the surface of the moon, Lyman and Kweskin asked their old bandmate Maria Muldaur to record some vocals on their new music. She recalled the “cosmic session” in the book Baby Let Me Follow You Down: “It was the day of the first moon landing. I'll never forget that...the moonwalk was happening on the television in the other room. We kept going in and out. There was this whole trip about how portentiously cosmic this all was. That night, we did 'People Get Ready,' and it was really beautiful, and Mel had tears in his eyes.” In this interpretation of the Curtis Mayfield 1965 political/spiritual anthem, Maria and her husband Geoff deliver a soft-spoken, moving vocal delivery backed by Mel Lyman, Jim Kweskin, Terry Bernhard, Richie Guerin, and studio engineer Billy Wolf. The arrangement is so quiet and sparse that the sounds of people adjusting themselves in their chairs is audible at various points; it is a remarkable 8 minutes of music. This track, and the rest of the Petrucci & Atwell sessions would be scrapped for reasons unknown, but the song found a place in the "Birth" bootleg which captures six songs from this abandoned project. For all the musical chemistry the Muldaur's found with their old friends that night of the lunar touchdown, it would soon be soured by another attempt to bring them up to Fort Hill and officially into the community. “We think we'll pass, thank you,” they replied in a tone that suggested the decision was final.

“Astral Weeks” (Live in Boston, 1972) – Van Morrison

Van Morrison doesn't perform the title track from his 1968 masterpiece at concerts very often. It's easy to understand why; the studio recording is so singular, so unreproducible, that it almost makes live attempts futile. But, on nights where Morrison is willing to reinvent the classic song of rebirth, the tune can itself be born again. Take this 1972 interpretation of it in Boston, for instance, where stretched-out, Grateful Dead-esque guitar solos are just as vital as Morrison's vocal delivery. The song's signature flute gets swapped out for saxophone. The studio take's shaker percussion is replaced here with a subtly played full kit, and it all works. Like so many of my favorite live recordings, the audience chatter picked up by the bootlegger's microphone only add to the charm—repeated listens turn the captured off-hand remarks into musical phrases integral to the song in that frozen moment. The photograph of Van Morrison and Peter Wolf in the center section of the book was taken before this performance. This is a song about searching out your soul mate after being reincarnated—has any other album ever begun that way? I don't think so, but maybe most records should.

“Strangler in the Night” – The Bugs

Is this the most offensive song ever recorded? I think it very well may be. Don't misunderstand, this is not an issue about being sensitive to dark subject matter. The problem here is that this is novelty record meant to profit off the confessions of The Boston Strangler—a phantom killer who took the lives of thirteen women in the early sixties. At least that was the marketing angle. The Astor Records sleeve says it all: “These are my thoughts, feelings, and emotions” followed by the signature of Albert DeSalvo, the man who confessed to the stranglings. Over two minutes of a generic 50's chord progression performed by a Marlboro band called The Bugs, WEEI radio personality Dick Levitan recites what is claimed to be DeSalvo's own words: “My body is reckless, my mind unaware / in these moments of madness I bite, claw & tear.” But is any of this true? According to Arf Arf Records head Erik Lindgren, no, it's not. Lindgren explained that the song was “actually written by a ghost writer, James Vaughn, who got drafted three weeks after the making of the single.” Why anyone involved agreed to this grim facade is unclear, but if money was the goal, no one was satisfied with the results; The record was a flop. But “Strangler in the Night” would be a drop in the bucket compared to the other ways people tried to cash in on the horrors associated with the Boston Strangler.

“The Red Sox Are Winning” - Earth Opera

Peter Rowan wrote “The Red Sox Are Winning” in 1967 as a Vietnam War protest while the local baseball team was, indeed, winning. Its multiple genres stitched together by the solid songwriting and production techniques make it hard to place, inspiration wise; it's a wild three and a half minute ride. In an odd way, this track is probably the best example of a sixties rock song about Boston, written in Boston, to come out of Boston. But it completely pales in comparison in popularity with the two hits from the era associated with the region, both still well known to this day—The Standell's “Dirty Water” and The Bee Gees' “Massachusetts"—which ironically were written by people with barely any connection to the area. In the case of 1967's “Massachusetts,” Robin Gibb had never set foot in the state when they wrote the song, remarking later, "We have never been there but we loved the word and there is always something magic about American place names.” The song went to #1 in the UK and Japan. Meanwhile, Ed Cobb wrote “Dirty Water” to be performed by a band from Los Angeles that he managed called The Standells. Cobb had been to Boston once, and during his visit he was mugged, according to The Standells who released the track in 1965. The entire song is a wry litany of complaints about the city including references to The Boston Strangler, the repressed nature of the city's women, and the filthy, shameful condition of the water in the Charles River. While the song peaked at #11 on the Billboard singles chart in 1966, it found another life in the 1990's when The Boston Bruins and The Red Sox began playing the song at games as a positive, rallying ode to the city. Whether the people singing along to “Dirty Water” at Fenway Park no longer hear it as a subtle take-down of Boston, or just don't care, is unclear, but there is something deeply ironic about this all circling back to Fenway, where Rowan wrote about a sea of citizens ignoring an atrocity in 1967 in a song that's now largely forgotten.

Ryan H. Walsh and Astral Weeks links:

the author's website

the book's website

excerpt from the book

Kirkus review

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette review

Spectrum Culture review

Boston Magazine profile of the author

Boston Globe profile of the author

Vanyaland interview with the author

also at Largehearted Boy:

Support the Largehearted Boy website

Book Notes (2015 - ) (authors create music playlists for their book)

Book Notes (2012 - 2014) (authors create music playlists for their book)

Book Notes (2005 - 2011) (authors create music playlists for their book)

my 11 favorite Book Notes playlist essays

Antiheroines (interviews with up and coming female comics artists)

Atomic Books Comics Preview (weekly comics highlights)

guest book reviews

Librairie Drawn & Quarterly Books of the Week (recommended new books, magazines, and comics)

musician/author interviews

Note Books (musicians discuss literature)

Short Cuts (writers pair a song with their short story or essay)

Shorties (daily music, literature, and pop culture links)

Soundtracked (composers and directors discuss their film's soundtracks)

weekly music release lists