« older | Main Largehearted Boy Page | newer »

May 22, 2018

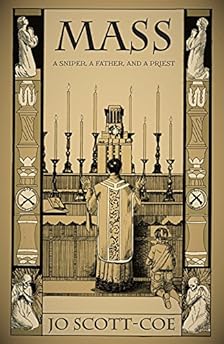

Jo Scott-Coe's Playlist for Her Book "MASS"

In the Book Notes series, authors create and discuss a music playlist that relates in some way to their recently published book.

Previous contributors include Jesmyn Ward, Bret Easton Ellis, Celeste Ng, Lauren Groff, T.C. Boyle, Dana Spiotta, Amy Bloom, Aimee Bender, Heidi Julavits, Hari Kunzru, and many others.

Jo Scott-Coe's MASS analyzes the 1966 University of Texas sniper case through the lens of the shooter's relationships with his father and priest.

A. W. Richard Swipe wrote of the book:

"Is there any connection between religion and mass murder? Scott-Coe analyzes the example of the then-most deadly televised American rampage—the Whitman case in 1966. She extrapolates the essential elements that help us understand current tragic events with the insight of an investigative reporter and the skill of a novelist."

In her own words, here is Jo Scott-Coe's Book Notes music playlist for her debut book MASS:

MASS took me six years to complete. At first, I thought the story was going to be a chapter in another book. I thought that it would be a straightforward narrative about how a public massacre privately impacted a religious figure. What I discovered was more fraught and much more layered. I had a lot of learning to do. The world already knew that a suicidal Charles Whitman took his guns atop the UT Austin tower on August 1, 1966, killing 15 and wounding 31. We already knew how hours before that, he fatally stabbed his mother, Margaret, and his wife, Kathy, in their beds with a brand new knife.

But I learned that one week before the killings, Rev. Joseph Leduc, the whiskey priest who had been Whitman’s scoutmaster and who presided at his Texas wedding, had just accepted a military chaplaincy assignment in Alaska. Following a tip describing Leduc as the most significant confidante in Whitman’s twenty-five years of life, the FBI located the priest and interviewed him two weeks after the shootings.

My quest to understand this man, who had died at a relatively young age in 1981, required a broad scope of research across Leduc’s pathway—from Connecticut to Canada, from Florida to Maryland and back to Florida, to Texas and Alaska and back to Texas again, then back to Florida. Each fragment revealed what had been too easily lost in the shuffle. There was much to find in plain sight, among systems of men who easily exploited the rules—in the military, in the church, and in white southern society—to protect their own interests. I put myself smack in the middle of it all, as a stray Catholic writer and as a woman who did not belong.

My playlist follows.

Sanctus (from Missa Luba, recorded 1958)

This liturgical hymn comes from the Latin (Tridentine) mass rite, performed and recorded on an album by Les Troubadours de Roi Baudouin, a choir of children and adults in the Congolese town of Kaminga. This variation of the hymn captures the influence of vernacular and local tradition seven years before the conclusion of Vatican II, when the Latin liturgy would be translated into local languages across the world. This specific track also haunts the cruel white colonial order of the prep school depicted in Lindsay Anderson’s film, If… (1968), a film that ends with a gun massacre staged from the top of a campus building.

The Right Profile, The Clash

This paen to Montgomery Clift starts with the question, “Hey, where’d I see this guy?”—a puzzlement that echoed my problem seeking Whitman’s priest, and worked as a kind of thread throughout conversations with others who had known/thought they’d known Rev. Leduc and all my doubling-back through archives and articles. Until I located Leduc’s picture, my fantasy understudy was Clift’s handsome and noble Father Logan in Hitchcock’s suspense film, I Confess, an image that turned out to be completely incongruous with Leduc’s actual face and character. What is the “right” profile for a priest? For anyone? Clift struggled with sexual identity, with drinking and with pills—all details that made him a troubled, elusive figure despite his often-serene image onscreen. There was the famous car accident that disfigured him so horribly. I later learned that he died in 1966, one week before the UT Austin shooting. Some refer to Clift’s death as a slow suicide, itself an echo of Leduc’s decade-long deterioration.

In Bloom, Nirvana

This tune—its insistent, slow grinding of a musical jaw juxtaposed with Cobain’s horn-rimmed, clean cut pale face in the video—for me works as an anthem to our ominously ordinary love affair with guns, the palimpsest of blood over a blurry self-image, an American death trap. Like the character in Cobain’s lyrics, we “don’t know what it means.” It’s easy enough to protest the lone gunman and his military grade small arms turned against us. But we ask less often about the war machines and remote controlled bombing devices we all already own, about the horrors performed in our name.

Sinnerman, Nina Simone

I discovered so much running around and scurrying and squirreling in MASS: Away from family problems. Away from accountability and obligations. Inside institutions and away from them. Away from properties and debts and jobs, from promises to wives. Whitman’s crimes are the most awful opposite of scurrying, an in-your-face violent performance on a mass stage. “Run to the rock,” as the song says—or run to the tower. There’s no hiding from the man who’s hiding from himself. Nina’s voice knows the sinnerman needs water for conversion, for a true connection with the Lord. Whitman chose fire and fury instead. And Rev. Leduc, the priest who loved to fish: the sea didn’t save him, either.

Stabat Mater Dolorosa (various)

This Catholic hymn to honor the suffering of Mary, and by extension, the suffering of all women, has its origins in the 13th century. The simple melody is a forlorn, Gregorian-like chant. It has been arranged and recorded by many artists, but I remember it most vividly as an a capella melody sung over and over during Lent by untrained voices, most of them kids, during the Stations of the Cross after school or after a short evening mass. In the little pamphlets we used, the verse at each stage of Christ’s pathway to crucifixion was to be sung “to the tune of Stabat Mater.” My writer’s ear has come to hear this direction as, “brutality and torture, set to the tune of women forced to watch.” This is a song for women (and children) who are witnesses, whose testimony is discounted, who are left with the mess that damages them.

The Harry Lime Theme from The Third Man, Anton Karas

American writer goes looking for man-crush college friend in the rubble of Vienna after WWII. American discovers friend is dead, then that friend isn’t dead, rather quite alive and callously criminal. Everyone ends up in the sewers, all secrets finally exposed, and a gun goes off. At the very end, the lady love-interest walks out of the frame, leaving the all the men in their bombed out graveyard. Graham Greene, whose whiskey priest is the center of his novel The Power and the Glory, authored the screenplay. Greene reportedly had a happier ending in mind, but later decided that the director, Carol Reed, got it right.

Sweetheart Like You, Bob Dylan

Bob Dylan’s song asks a question I faced again and again as I wrote. It wasn’t interrogation, just dismay. The central women in this story, and in too many stories like these, deserved better men—better partners, fathers, priests, ministers. Better workplaces and better contracts. Better law enforcement and better medical care. They deserved more than men who simply would not murder them. They deserved men who saw and heard them, took them seriously, and believed what they said.

Take Me to Church, Hozier

Hozier turns the title refrain inside out, with the lyrics calling us to a different kind of ritual, between intimate partners who have too long been shamed by institutions and brutalized by men who act in their name: “Every Sunday’s more bleak/A fresh poison each week./’We were born sick’/You heard them say it.” The song is a powerful indictment of wounds—both emotional and physical—inflicted in the name of religious rules, especially about marriage and sexuality.

Kiss Off, The Violent Femmes

Here we start with a frantic plea for counseling or connection: “I need someone a person to talk to/someone who’d care to love/could it be you.” It turns sour fast. The UT massacre took place in 1966, the same year Jacqueline Susann’s chemically infused novel, Valley of the Dolls, was published. Investigators discovered Charles Whitman to be a serious self-medicator, not through alcohol (Leduc’s apparently preferred substance) as much as pills, whether prescribed through doctors or not. Given the ethos of the time, however, none of this is especially shocking. In this song, Gordon Gano’s voice builds to a litany of ten angry doses—the ninth pill for “the lost God,” and the last one, climactically, “for everything everything everything everything.” With the “kiss off into the air,” we know that the pharmaceutical solution will not hold, that all these little bullets only lead to the brink of a punishing, dangerous rant.

Hurt, Johnny Cash

The last track for MASS goes to the Man in Black, aka Johnny Cash, with his cover of the NIN song. There were a lot of “men in black” I consulted for this project—aging priests and former priests, friends and family members who had endured decades of unimaginable grief. Here is the voice of the onetime outlaw-addict, the man who knows that ash awaits us all, his song pulling us back from an edge he has seen so clearly. “What have I become/my sweetest friend?” is not a question Whitman wanted to answer. Brutality against his wife and mother, against total strangers—horrific acts demanding that ultimate harm would come to himself—all took the place of transformation and redemption. Cash’s voice calls out to us across generations of graves remembered and forgotten, suggesting a different lesson: “If I could start again/a million miles away/I would keep myself/I would find a way.” Here is another elusive rite we might reach towards, a better “if,” far away from empires that demand blood as a daily offering.

Jo Scott-Coe and MASS links:

Superstition Review interview with the author

also at Largehearted Boy:

Support the Largehearted Boy website

Book Notes (2015 - ) (authors create music playlists for their book)

Book Notes (2012 - 2014) (authors create music playlists for their book)

Book Notes (2005 - 2011) (authors create music playlists for their book)

my 11 favorite Book Notes playlist essays

Antiheroines (interviews with up and coming female comics artists)

Atomic Books Comics Preview (weekly comics highlights)

guest book reviews

Librairie Drawn & Quarterly Books of the Week (recommended new books, magazines, and comics)

musician/author interviews

Note Books (musicians discuss literature)

Short Cuts (writers pair a song with their short story or essay)

Shorties (daily music, literature, and pop culture links)

Soundtracked (composers and directors discuss their film's soundtracks)

weekly music release lists