« older | Main Largehearted Boy Page | newer »

August 25, 2020

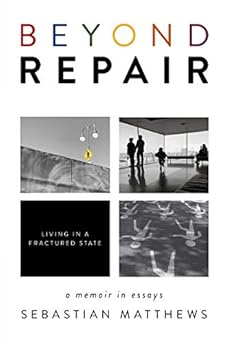

Sebastian Matthews' Playlist for His Memoir "Beyond Repair"

In the Book Notes series, authors create and discuss a music playlist that relates in some way to their recently published book.

Previous contributors include Jesmyn Ward, Lauren Groff, Bret Easton Ellis, Celeste Ng, T.C. Boyle, Dana Spiotta, Amy Bloom, Aimee Bender, Roxane Gay, and many others.

Sebastian Matthews' memoir-in-essays Beyond Repair is inventively told and incredibly moving and timely.

Beth Ann Fennelly wrote of the book:

"Beyond Repair: Encounters in a Fractured World is a portrait of community in traumatized times. Sebastian Matthews documents dislocation, both psychic and physical, in these tightly crafted nonfiction vignettes. Whether the speaker is on the sidelines at his child’s soccer game, seeking help from the credit card fraud hotline, or in the elevator with a confused Alzheimer’s sufferer, Matthews enacts the difficulty and necessity of compassion. With wryly insightful observations, Beyond Repair brings us closer with every sentence to the deep repairing we need."

In his own words, here is Sebastian Matthews' Book Notes music playlist for his memoir Beyond Repair:

Beyond Repair is told through a series of encounters with friends and neighbors, colleagues and strangers, from early 2014 to spring 2019. It tells the story of my re-emergence after having survived and recovered from a major car accident. When I finally returned to the world—as father and husband, friend and brother, writer and citizen—it became clear that the world was trapped in its own traumatized state—reeling from one after another police shooting of unarmed African-Americans, stunned by yet another mass shooting—and that everywhere people were displaying signs of PTSD. My interactions in daily life became more and more dysfunctional, at times downright hostile—us against them, red vs. blue, black vs. white, rich vs. poor. That my family and I live in a progressive town inside a conservative county in the mountain south only made things more volatile.

In response, I decided to re-engage with the world in the posture of a reporter looking for a story, attempting to encounter men and women in cafes and bars, in gas stations and dance clubs, on airplanes and city streets. My goal was to enter into these experiences as conscious as possible of the potential divides and misunderstandings between us—including my own unearned privilege as a middle-aged white man—while working to make meaningful connection. I started with my neighborhood and town, then moved out into the surrounding counties, then traveled further out into the country and wider world. At the same time, my wife and I were working to raise our teenage boy, doing our best to help him navigate this new environment.

Bob Marley & the Wailers, “Three Little Birds”

The book opens with a description of a drive I took from Chattanooga to my home in Asheville, North Carolina. Only three years out from the accident, I was still struggling with driving on highways, and memories of our collision would often force me off the road. On this occasion I ended up driving over the mountains via back roads. Along the way, I kicked out an old Bob Marley tape from under the seat and plopped it in the rarely used tape deck. “Three Little Birds” came on just as I was coasting down the last back road, its mantra of “everything’s going to be all right” ringing in my chest.

The Impressions, “Keep on Pushing”

Later that year, I went to see Selma with a close friend. We held hands through the most violent parts of the movie and cried together. This experience deepened our friendship in that my friend, a Black woman, could see that I understood, at least in part, the injustices she has faced, and still faces, in this country.

There’s no mistaking Curtis Mayfield’s soulful tone, and his unique style, even his early days with the Impressions.

Al Green, “What a Friend We Have in Jesus”

I became something of a hermit in the years it took to recuperate from the accident. After a few years, I finally got up the nerve—and energy—to fly to New York to see my aunt. Usually I’d take a cab from the airport, but on this occasion, having landed at JFK, I decided to take the subway from Queens into Manhattan. It was an uneventful ride on one level and deeply moving on another. Having been living a relatively sequestered life in mostly white Asheville, sitting with so many black and brown people made me happy. I hadn’t realized how much I’d missed the diversity of a true city.

A little before the tunnel a young man entered our car and sang us some gospel tunes for spare change. “What a Friend We Have in Jesus” was his final tune. Why not let the Reverend sing it for us here?

King Sunny Adé, “Sunny Ti De”

Soon after the New York trip, I attended a conference in Minneapolis. One night, a group of friends stumbled upon a quaint Ethiopian restaurant tucked in an old brick building. It was getting late, and the waitress seated us in the last open table. By the time we got our meal, things had thinned out. Most of the crowd at this point were friends and family of the restaurant owners. The speakers played some lovely Word Beat music and children danced in the aisles.

I can’t remember the exact music that was playing that night, so I will go with an old favorite, South African jùjú master, King Sunny Adé. I’d been listening around then to his compilation The Best of the Classic Years, as you will see below.

Culture, “Chant Down Babylon”

About two years out from the accident, we hired a friend to build a writing studio in place of an unused garage. Carl was married to a colleague of mine, and we’d all hung out a few times at each other’s houses. Carl and Catina had moved to Asheville from Brooklyn, but Carl was originally from Grenada. We shared a love for reggae and African music. I played him King Sunny and Bunny Wailer; he played me Mikey Spice, Lucky Dube, and Culture. During the months it took for Carl to complete the job—he did beautiful work on the space—I’d often take a break from my writing to share a beer with Carl or shoot hoops out in the driveway. Of all the songs we played during this idyllic time, “Chant Down Babylon” echoes most clearly in my head.

Mavis Staples, “Slippery People (Live)”

The day after Trump got elected, my buddy Jay and I went to hear Mavis Staples perform at the Orange Peel in downtown Asheville. It had been a long, dark hangover of a day, and we had almost talked ourselves out of going.

Indeed, the crowd was subdued through the opening act and into Mavis’ first few songs. But Mavis talked us out of our gloom, promising hope and transformation, urging us to keep fighting. By the time the band broke into the Talking Heads’ “Slippery People” the joint was rocking. I boogied in the back and sang along: “you best believe this thing is real.”

Jason Moran, “Thelonious”

My wife and I caught a Lorna Simpson exhibit in Andover, Mass. Her parents had lived there for years, and we often checked out the Andover Academy Museum on our visits. It’s a surprisingly high-level, innovative museum.

I’d heard of Simpson but wasn’t all that familiar with her work. Needless-to-say, the show blew me away. There was an especially moving piece entitled “Chess.” You entered into a dark room filled with a set of wall-sized projections. On one wall, a man and a woman played chess. Each character was refracted in a five-way mirror. (Simpson was the actor for both!) Opposite, pianist Jason Moran was playing a piece he composed for the installation. One screen showed his right hand playing, the other his left. It truly felt like you were inside a hall of mirrors. The tune here is not from that show; it’s his tribute to Thelonious Monk, which appears on the album Ten.

Lil Jon & the Eastside Boyz, “Get Low”

With a friend as a guide, I’d gotten involved with Callaloo, a journal of African Diasporic Literature and Art. I attended a few days of their conference down in Atlanta the year before and most of the conference in Providence, Rhode Island. I was happy (and honored) to be invited to come as a guest at one of their workshops down in Chapel Hill. After the discussion, a group of writers and scholars gathered at the Carolina Inn for rounds of drinks. The talk was heady and exhilarating, touching upon a range of subjects, from The Odyssey to Michael Brown’s murder to Black Futurist literature. It was getting late, and the bartender finally turned off the lights and shooed us out.

I was walking my way back to my hotel, more than a little drunk, when a car creeped past, Lil John’s “Get Low” blasting loud, bass thumping down the street. I went to sleep with its incessant chorus chiming in my head.

Christian McBride, “Listen to the Heroes Cry”

By this time, I was travelling to New York twice a year, for business and to see family and friends. My aunt lives in the West Village, so I’d often stay in a hotel in Chelsea, heading down to catch a show at The Village Vanguard with her if when I could. And though it was just last year that a bevy of friends and I saw Christian McBride & the Inside Straight, that set feels representative of the whole time.

Mississippi Fred McDowell, “You Got to Move”

Callaloo held its next conference in Oxford, England. I’d been asked to speak on a panel. After the night’s main reading, a large group gathered in the hotel pub. At some point late into the evening, a poet pulled out a harmonica and lead the group in a soulful, mesmeric rendition of “You Got to Move.”

Stevie Wonder, “Boogie on Reggae Woman”

At some point in this story, my son and his best friend started calling me “White Dad.” It started because I was wearing a pair of sneakers that they deemed “White Dad shoes.” The more I tried to convince them that they were cool shoes (bought in a Montreal boutique), the more they asserted the fact. It became a running joke between us. (Me: You’re a White Dad. Avery’s friend, Phoenix: I can’t be a White Dad, I’m Black.” Me: “But you’re acting like a White Dad.”) In the end, all I could do was put on Stevie Wonder and embrace the truth.

Keep It Gullah, “High Killah/Killah High”

During a week down at Folly Beach, South Carolina, we stumbled upon an authentic Gullah restaurant out on Mosquito Island. The food was great, the atmosphere laidback and local. One of the patrons came over and welcomed us, giving us an impromptu history of the Gullah community that had settled there hundreds of years back. I took a walk after the meal, passing a tiny nightclub called the Def Club. And as we were getting to leave, a group of young men and women arrived at the club for a night of dancing. I remember distinctly the feeling of being an outsider—a tourist trying to tread lightly and respectfully, hoping to be not so much a trespasser as a welcomed guest.

I found this cut while searching online for “Gullah hip hop.” I am not sure Keep It Gullah has ever performed at the Def Club, but I can imagine the young men and women driving up to that backwater joint blasting it through their speakers.

Dirty Dozen Brass Band (with G Love), “Mercy Mercy Me”

During the four years that it took to write this book, as catastrophe after catastrophe hit our country, both manmade (mass shootings, police killings of unarmed black men and women) and natural (fires, floods, earthquakes), the memory and after-effects of Katrina kept echoing. More than once I pulled out this tribute album/relief effort project. What better move than to redo Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On? song by song? What better songs than “What’s Going On?” and “Mercy Mercy Me” to speak to all the chaos and tragedy and strife swirling around. Now more than ever.

Charles Bradley, “Changes”

I heard Charles Bradley sing this song at the Lake Eden Arts Festival (LEAF) the year before he died. He came on at the end of the festival’s big night. I was sitting at the back edge of the crowd sipping a beer in my camp chair. Stars were coming out in the night sky, reflecting in the water behind us—everyone blissed out and exhausted after a long day in the sun. Bradley was pouring out sweat as he belted out the words: “But soon the world/ Had its evil way// My heart was blinded/ Love went astray.”

Lil Baby, “Catch the Sun”

I have been listening to my teenage son’s music more and more. It helps to get to know him a little from the inside out.

During a recent argument, for instance, Avery pulled out his phone and asked me to listen to a Lil Tj tune. This is how I feel, he told me without having to tell me, sitting there and chanting along with the lyrics: “I just want my name to be around when I ain't here/ Livin' in the moment, but I want this shit for years..”

He didn’t have to explain. I knew that he was trying to assuage the doubt, the anger, the anxiety—the whole ball of mixed-up confusion—of being a sixteen-year-old in high school, trying to fit in and find his people. It’s there in the music. In his sharing of that music.

Even though it came out after I completed this book, I am selecting Lil Baby’s “Catch the Sun” for the last song of this playlist. The final piece in the book, “Shooter,” describes sitting in line to pick Avery up after school on the one-year anniversary of the Parkland shooting. There were a half dozen songs that Avery played heavily off his playlist that spring (blasted as we drove back and forth to school), but still it is “Catch the Sun” that comes to mind when I recall those anxious post-Parkland days. Something about that haunting melody, the ache in the lyrics, the desperate hope the song carries. It feels like an anthem to me—for my boy, for his generation. An anthem, but also a dirge.

Sebastian Matthews is the author of a memoir, In My Father’s Footsteps, and two books of poetry, We Generous and Miracle Day. His hybrid collection of poetry and prose, Beginner’s Guide to a Head-on Collision, won the Independent Publisher Book Awards' silver medal. Matthews is also the author of The Life & Times of American Crow, a “collage novel in eleven chapbooks.” His work has appeared in or on, among other places, the Atlantic, Blackbird, the Common, Georgia Review, Poetry Daily, Poets & Writers, the Sun, Virginia Quarterly Review, and the Writer’s Almanac. Matthews lives in Asheville, North Carolina. Learn more at sebastianmatthews.com.

If you appreciate the work that goes into Largehearted Boy, please consider making a donation.