« older | Main Largehearted Boy Page | newer »

April 5, 2021

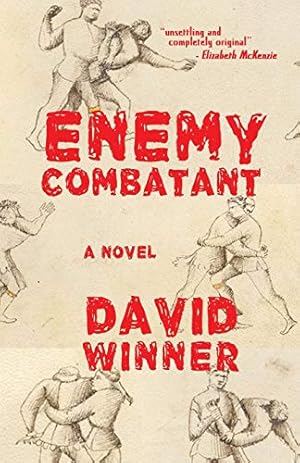

David Winner's Playlist for His Novel "Enemy Combatant"

In the Book Notes series, authors create and discuss a music playlist that relates in some way to their recently published book.

Previous contributors include Jesmyn Ward, Lauren Groff, Bret Easton Ellis, Celeste Ng, T.C. Boyle, Dana Spiotta, Amy Bloom, Aimee Bender, Roxane Gay, and many others.

David Winner's novel Enemy Combatant is a compelling, innovatively told literary thriller.

Kirkus wrote of the book:

"A searingly insightful, tragicomic adventure that lays bare personal and political fault lines. ."

In his words, here is David Winner's Book Notes music playlist for his novel Enemy Combatant:

We Will Rock You

In the early seventies when the father of a friend from Yorkshire forbade him his beloved Beatles and Stones because he considered it “jungle music,” my friend began to view rock and roll as the ultimate music of rebellion. As much of a fan of “classic rock” as I am, I’m not sure it seems so rebellious these days. In fact, it comes comes off as malevolent establishment music in Enemy Combatant, a dark (if comic) signifier of American evil. In the Lori Valley of Armenia, Leonard and Peter trail a black armored van that they believe is driven by two members of the American military on its way to what might be a CIA black site. Queen’s “We will rock you,” bursts forth from the van’s stereo system. I think Freddy Mercury had in mind something about individualism and freedom, which could mean beating the crap out of people suspected of being enemies of America.

“Buddy, you're an old man, poor man,” sings Freddy Mercury.

“Pleading with your eyes, gonna get you some peace someday

You got mud on your face, big disgrace

Somebody better put you back into your place, do it.”

For L and P, my protagonists, the buddy they’re putting their place could be an American soldier. For the America soldiers, the buddy might be a prisoner captured in Afghanistan who may or may not have anything to do with Al Qaida.

Flirting with Disaster

Early the following morning, Leonard and Peter encounter another American soldier at an abandoned copper smelter that has been requisitioned by the United States. The soldier is too lost in the song that he’s listening to on his iPod to hear them approach, which gives them the element of surprise.

The novel doesn’t reveal that he’s listening to “Flirting with disaster” by Molly Hatchett. Growing up Chicano outside of Richmond, Virginia, the soldier (the novel fails to name him, but let’s call him Joe) had to be more of a good old boy than the good old boys surrounding him to have any chance of fitting in. He ended up in the military to try to stop the kind of behavior that the song relates.

Speeding down the fast lane, honey

Playin' from town to town

The boys and I have been burnin' it up, can't seem to slow it down

I've got the pedal to the floor, our lives are runnin' faster,

Got our sights set straight ahead,

But ain't sure what we're after

But when Joe took a high-paying security job overseas a few years later, he didn’t realize that then he would really be “flirting with disaster.”

Jamel_AKA_Jamal on a YouTube reaction video suggests that the Hatchet are crying “out for help, having issues.” “If you are in this with me,” he says of the song, “then buckle up.” He chooses not to dwell on what, as a black man, might seem obvious, how much more deadly this kind of disaster on the highway could be for the likes of him then white southern boys like the Hatchett.

Friend of the Devil

After the darkest moment of the novel, a frightening action for which the protagonists are more than a little responsible, they are driving on a small road in a car they’ve stolen. Listening to the radio.

I was in Armenia a couple of times, but I didn’t get much of a sense of what was on the airwaves. Armenian and Russian pop probably dominate, but as king DJ in my own novel, I played “Friend of the Devil.”

The narrator of the song is running away from women, law enforcement, hounds and the devil, one of those sympathetic American outlaws, beleaguered in an alienating world.

And the words, fractured by the bad reception in and out of the hills through which the car is driving, feel eerily resonant for Peter and for Leonard as if the gods of Armenian radio know exactly the terrible event that has just occurred.

lit up from Reno

trailed by twenty hounds

sleep that night

morning came around

I set out running

A friend of the devil mine.

If I get home before daylight

might get some sleep

Politicians in my Eyes

Early in the novel when Peter’s mother dies in a botched surgery, Peter focuses his rage not so much on the doctors responsible but on the president of the United States, George W. Bush, with whom he has been fanatically angry since soon after 9/11.

One evening, after his wife has gone to sleep, he drinks cheap white wine, inhales powerful weed, and plunges deep into his laptop looking for information about Abu Ghraib, Guantanamo.

A band called Death is cranked in his ears, and he mouths their words to himself.

Always tryin' to be slick when they tell us the lies

They're responsible for sending young men to die

We have waited so long for someone to come along

And correct our country's law, but the wait's been too long

His wife wakes up from an impenetrable dream to hear the sound of industry like someone is drilling right nearby, which soon turns into what it actually is, guitars, and she hears her husband’s reedy tenor voice screaming about how “sickening” it is to “to see the way they lie on TV.”

She takes the paperback murder mystery that she had been reading and fires it powerfully against the bedroom door to try to get him to shut the fuck up.

But it’s a hopeless cause. Death is blasting in his ears and he’s too preoccupied to hear anything coming from outside himself.

Come on Feel the Noize

The employing of rock music as a kind of torture has a storied political history in the United States. Death metal was apparently cranked at Guantanamo to try to shatter prisoners’ defenses, and when Manuel Noriega, was hiding out in the Holy See in Panama City during Bush I’s invasion, American soldiers cranked “You shook me all night long,” by AC/DC and “Welcome to the Jungle” by Guns N’Roses to try to drive him out.

Taking off on that idea is another grim scene from my novel in which Peter, by himself this time, is climbing a steep, vine-filled hill towards a place in the Republic of Georgia where he’s seen more American soldiers, driving back and forth.

In the distance, he hears a song that he later comes to recognize as Quiet Riot’s popular cover of “Come on Feel the Noize.”

So cum on feel the noize

Girls grab the boys

We get wild, wild, wild

We get wild, wild, wild

So cum on feel the noize

Girls grab the boys

We get wild, wild, wild

At your door

The noise can only frighten the injured, sleep-deprived prisoners held atop the hill. And they don’t particularly appreciate being invited to a 1980’s American sex and rock and roll party.

What’s Love Got To Do with It?

Scenes cut from movies can sometimes be returned (usually a mistake) in director’s cuts, but what about scenes cut from novels? They only live on in the writer’s mind or the editors who’ve offed them.

One cut scene that plays in my mind is a moment from Leonard and Peter’s night of debauchery in Kas, a Turkish seaside town. That leads to Peter’s escape from Leonard to neighboring Georgia, which he imagined (wrongly) would give him some piece of mind.

A friend from Turkey did a little research for me, and concluded that, yes, cocaine is or, at least, was available in that country with famously draconian drug laws.

And Leonard, majorly decompressing after losing his job back in America, has managed to locate some.

He and Peter, dining at an expensive seafood restaurant looking out over the Mediterranean, can only play with their food.

Leonard is on his way back from the bathroom, where he’s availed himself of more of the product. On the restaurant stereo, Tina Turner demands to know “What love got to do with it?” And Leonard awkwardly wiggles his buttocks, sashays his hips, and sings along, acquiring skeptical stares from the other diners.

“What’s Love got to do with it, indeed” wonders Peter, beginning to come down from the drugs.

His wife seems further from him than ever, and he can only look at Leonard with contempt.

It Goes Like It Goes

Tears are in Peter’s forty-two-year-old father’s drunken eyes and Peter’s twelve-year-old sober eyes as well, as Jennifer Warren sings

Ain't no miracle bein' born

People doin' it everyday

Ain't no miracle growin' old

People just roll that way

So it goes like it goes and the river flows

And time it rolls right on

And maybe what's good gets a little bit better

And maybe what's bad gets gone

the title track to Norma Rae while the credits roll. Peter’s father pours just a little more bourbon in his glass and promises his rapt son that they would drive down from Virginia to North Carolina to find that “asshole mill town” even though they’d miss days of work and school. They’d make sure the “faggot” owners hadn’t broken Norma Rae’s union.

Peter jumped out of bed early the next morning and checked his parent’ bedroom every ten or fifteen minutes for signs that his dad was rising.

Peter had packed his blue suitcase with clothes for the journey south along with toiletries and schoolbooks, so he wouldn’t fall too far behind.

But when the old man struggled out of bed around eleven, he’d glared glassy eyed at Peter so witheringly that Peter could tell the deal was off.

If you appreciate the work that goes into Largehearted Boy, please consider making a donation.