« older | Main Largehearted Boy Page | newer »

July 21, 2021

Maureen N. McLane's Playlist for Her Poetry Collection "More Anon"

In the Book Notes series, authors create and discuss a music playlist that relates in some way to their recently published book.

Previous contributors include Jesmyn Ward, Lauren Groff, Bret Easton Ellis, Celeste Ng, T.C. Boyle, Dana Spiotta, Amy Bloom, Aimee Bender, Roxane Gay, and many others.

Maureen N. McLane's poetry collection More Anon sharply declares her intellect and wit.

In her own words, here is Maureen N. McLane's Book Notes music playlist for her poetry collection More Anon:

More Anon: selected poems draws from five books of poetry. It includes work published between 2005-2017, written from the mid-90s onward, in places ranging from Chicago to Cambridge MA to New York City to London, Paris, Florence, New Hampshire, and the Adirondacks. Music wends its way through the book, as it has through my life, in a bunch of ways. There are direct allusion to songs, composers, ballads and ballad traditions, and there are glimmerings throughout of my ongoing interest in song forms like chanson, lieder, and blues. As I child I took piano lessons; I became a somewhat hapless teen church organist, nervously vomiting before masses (when playing for the local Catholic church) or, less frequently, before services (when playing for the lower-key Protestants who, unlike the Catholics, would sing). Moving through my mind then were church hymns and Bach preludes and chorales, alongside the Top 40 and FM radio of the 70s and 80s, pop, new wave, indie rock, some R&B and commercial hiphop. Suburbia!

In my twenties I sang in Chicago with an early music group, In Terra Vox; that repertoire and a longer history of choral and a capella singing formed one significant layer of my inner sound world.

Later on, studies of English, Scottish, and American balladry – and of the music of “the old, weird America” as Greil Marcus put it – flowed into my headspace: Child ballads, Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music, Alan Lomax’s recordings, Lead Belly’s repertoire, Jean Ritchie’s and other singers’ repertoires. Over the years I’ve had eclectic training and experience as a musician. Most important I think is the way these experiences encouraged me to listen . . . and the way different forms of study and listening opened me to varieties of voicing and sounding and to questions of timing, forming, and pattern.

Unlike some poets, I don’t – can’t – write to music; I need relative quiet, if not silence. For me that opens a space of receptivity.

All of my books have poems titled “Song” – “Song of the Last Meeting,” “Songs of a Season,” “Songs of the South” – and there’s a strong lyric element in them. One of my favorite lyrics is “Westron wynde,” an anonymous song usually dated to the sixteenth century: its tune threaded its way into several masses by English composers and also thrives via countless sung versions on YouTube. For me this long history of anonymous composition and remaking – of songs, ballads, and poems – is powerful and influential, a way to think about poetry as moving through you, not originating with you. (This is separate from the long vexed history of appropriation, by which songs, riffs, tunes, etc. have been expropriated from their makers.) For a playlist accompanying a book called More Anon, it’s worth saluting “anonymous”: as Virginia Woolf wrote, “I would venture to guess that Anon, who wrote so many poems without signing them, was often a woman.”

I tend to respond to works and periods when music and verse are closely intertwined – or perhaps most stimulating to me is the idea of this entwining: Sappho supposedly singing to a lyre, perhaps to and with a chorus of girls; troubadours (and contemporary rappers) with their vaunting, intricate, sometimes erotic, sometimes boasting lyrics; late medieval/early Renaissance forms like rondeaus, madrigals, motets, chansons . . . but I’m interested as well in story, in so-called ambient music, and those zones where music shades into “noise” on the one hand and notional “silence” on the other: hello John Cage, 4’ 33”.

The movement of inner voices compels me – all those years as a second soprano or (briefly) as a wrongly classified alto trained me to listen to inner textures, and also gave me the experience of what it means to be singing out of one’s ideal range: perversely useful countertraining for a poet as well as singer. Years ago, in various ensembles, I sang a lot of motets – from Thomas Tallis to Heinrich Schütz to Maurice Duruflé: to be partaking in that choral polyphony, largely unaccompanied, was for me a crucial experience of surround sound, of embodied and shifting co-vibration. That suspension and suspense in time, provisional dissonances en route to something, if not resolution: that’s part of my sensorium. Some favorite motets and favorite performers/ensembles: Tallis, “Tota Pulchra Es” (Tallis Scholars); Schütz, “Die mit Tränen säen” and “So far ich hin zu Jesu Christ” (Collegium Vocale); Duruflé, “Tota Pulchra Es.”

I’m attracted to composers who continue to explore this legacy in totally contemporary ways: Janet Cardiff’s “The Forty Part Motet” (an audio installation and reworking of Tallis’ 1556 “Spem in Alium”) comes to mind. I first heard it as an installation at the Met Cloisters. And I think too of Caleb Burhans, his album Evensong, and of a favorite track performed by the Trinity Wall Street Choir, “Super Flumina Babylonis.” And then there’s Missy Mazzoli’s riveting Vespers for a New Dark Age.

I remember hearing Roomful of Teeth perform at Le Poisson Rouge in 2013 – including the premiere of Caroline Shaw’s Partita for 8 Voices. Ever since: a huge fan. The movement from speech rhythms to a kind of choral wail and swoop and back, the wit, the exuberance and power of the ensemble . . . In the past couple of years I’ve listened a lot to Shaw’s album Orange, which includes the fantastic string quartet “Entr’acte,” which I first heard played by the Attaca Quartet at the Miller Theatre, Columbia University. The way her work holds or channels others’ work is also appealing (“Entr’acte” salutes a Hayden string quartet); it’s an analogy maybe for the way a poem can hold others’ voices and voicings, how rhythms and sounds precede us and can seize us, how citation can be part of a larger weave of co-composition.

Judah Adashi set one of my poems, “For You,” for voice and viola, and had Caroline Shaw and Caleb Burhans record the piece to play at his wedding: that was a thrill – you can listen to their recording on Soundcloud. Judah’s “my heart comes undone,” his gorgeous 2014 work for cello and loop pedal, has just been released as a track performed by his wife Lavena – part of her recently released debut album “in your hands.” And, back to citation and channeling, it’s maybe worth noting that Judah tips Björk’s “Unravel” as the musical point of departure for this piece.

Another contemporary composer and artist I admire: Meredith Monk. Some years ago a friend sent me tracks from Monk’s Volcano Songs: “Three Heavens and Hells” became a particular favorite, and somehow for me it resonates with William Blake and his visions. And I only recently discovered the work is based on a text by Tennessee Reed, the eleven-year-old daughter of Ishmael Reed! The piece features some classic Monk extended vocal techniques and is a wild ride. I’ve taken some workshops with Monk and her ensemble, including Katie Geissinger – I love Monk’s dedication to what she calls the dancing voice, the singing body. I love everything from her early freaky WGBH show “Turtle Dreams” (you can watch here! with a real turtle!) to her “Gotham Lullaby” from Dolmen Music to her opera Atlas (listen to, say, “Part I: Personal Climate: Choosing Companions”). Among the canons (rounds) she teaches are a few by Louis Hardin, aka Moondog, a fascinating figure in his own right. Some favored Moondog compositions: the canon I learned from Monk, “All Is Loneliness,” a pulsing instrumental piece, “Bird’s Lament,” and a high lonesome song, “High On A Rocky Ledge.” The last live music I heard before Covid lockdown was The Ghost Train Orchestra playing music by Moondog at Le Poisson Rouge: the concert feels so long ago, and yet also last night.

Live music has often offered me a gateway to new music and recurring obsessions – as when I heard Vijay Iyer and his trio at the Whitney (and then at the now-shuttered Jazz Standard) and soon began following Tyshawn Sorey’s work as well. Other gateways – John Schafer’s New Sounds on WNYC: thank god they walked back their cancellation of that show! Still other significant gateways: my former therapist had an amazingly catholic taste, and turned me on to Maria Bethânia (sister of Caetano Veloso), to various Malian masters of the kora, to Steve Reich’s “Come Out” (a composition in support of the Harlem Six, tried for murder in 1965). We shared an interest in Portuguese fado and in lieder singers like Fritz Wunderlich. My partner Laura is an opera aficionada and often plays chamber music, and we listen to a lot together. Another friend years ago sent me John Coltrane’s ravishing “Peace on Earth” and some Alice Coltrane tracks, including “Journey to Satchidananda.” I love her big orchestral swooping harp and organ shazam.

Simone Dinnerstein’s recording of Bach’s Goldberg Variations is something I’ve listened to ever since it was first released in 2007. I have so internalized her tempi that I can find it almost disorienting to listen to other brilliant pianists’ recordings of this work (Glenn Gould’s, Angela Hewitt’s). There’s a particular moment, the shift from the end of the 27th to the start of the 28th variation, that always registers for me, and only in Dinnerstein’s playing (slower than some others’, and not as hyper-articulated), as a physiological event, a kind of cosmic opening. I don’t have the precise musical language for what is happening here – but that feeling is one I cherish and both look forward to when listening and am each time surprised by. Building larger structures out of permutations and variations is something I’ve done in some longer works. Even at the level of refrain, I’m interested in the way returning things can still surprise us, or take on new implications as a work moves forward. There’s something enormously satisfying too if, when you get to the end of a work, a restatement of a theme makes you go wow, where have we been, and how did we get here, and yes.

As for what music explicitly made its way into poems: “The Riddle Song” (“I gave my love a cherry”) which wends its way through the close of my poem “Mz N Contemporary.” (I include Doc Watson’s version, and then Sam Cooke’s.) Beyoncé’s melismas, Al Green’s seductions. Ian Bostridge singing the songs of English Renaissance composer John Dowland. Some years ago, soon after hearing Bostridge in concert, I was looking at some Dowland scores in the British Library and was brought to wonder again, as I write in “On Not Being Elizabethan”:

How did they do it

shape their complex minds

into chiming lines

of woe & sorrow

crowning frowning

every rhyme sieved in time

to a bell they all heard ringing

Bostridge’s “Come Again, Sweet Love Doth Now Invite” was among several Dowland songs running in my mind. Another, performed by yet another singer I like, Emma Kirkby, was “I Saw My Ladye Weepe.” More specifically my poem quotes a lyric from Dowland’s “Can she excuse my wrongs” from his First Book of Songes or Ayres – a lyric often attributed to Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex: turns out that Queen Elizabeth did not excuse his purported wrongs, as he was executed. I include a version by countertenor Andreas Scholl, and a slightly alarming one by Sting.

My poem “Haunt” tracks many modes of haunting – by ghost stories, tales, gossip, poems, songs, war, broader horizons of violence (I was thinking of the Iraq War, amidst other things). En route the poem salutes murder ballads (see e.g. “Lamkin,” or “Little Omie/Oma Wise”) and weaves in lines from the English ballad “The Three Ravens” (definitively set in 1611 by Thomas Ravenscroft, and sung by many since). The poem closes with gruesome lines taken from a Scottish variant of “The Three Ravens,” called “The Twa Corbies,” as the two birds consider “pik[ing] out [the] bonny blue een” (“eyes” in Scots) of a dead knight. For an art song take on “The Three Ravens,” the 20th-century countertenor Alfred Deller is great, as is Andreas Scholl; for an intensely orchestrated version, listen to John Harle’s, sung by Sarah Leonard. Some other favorite ballads and versions: “Oma Wise,” in Peggy Seeger’s version; June Tabor’s stunning rendition of the (spoiler alert!) incest-suicide ballad “The Bonny Hind.”

I have a few playlists of ballad variants – for example of the love-and-kinship gone wrong song, the murder ballad “The Two Sisters,” also sometimes known by its refrain, ‘The Wind and Rain.” Nico Muhly and Sam Amidon have an amazing kind of deconstructed version of that ballad: “The Only Tune Part 1: The Two Sisters” (on Muhly’s Mothertongue – there are two additional movements as well). Other versions worth hearing: Jean Ritchie’s (called “There Lived an Old Lord”); the Irish traditional band Altan’s “Wind and Rain”; and then, for something really different, there’s the ragged growly feral Tom Waits version.

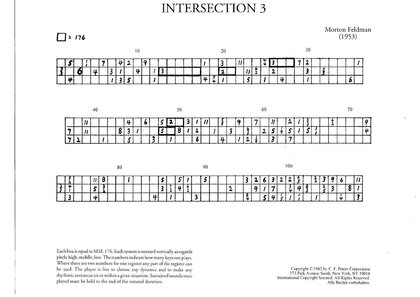

On the dead, revenants, violence (again): my poem “Headphones” pivots from the French Revolution to the Nixon administration to Morton Feldman hearing the voices of murdered Jews in Berlin. A piece I sometimes share with students: Morton’s “Intersection no. 3,” which also has a fascinating score to contemplate (here’s a section):

Some things I listened to and returned to over the years covered in More Anon: a playlist I call Old Timey Ladies featuring everyone from Allison Moorer to Gillian Welch to Lucinda Williams; another party playlist for dancing and NYC vibes – with Azealia Banks’ “212” (straight up raunchy sex-positive flair) and Angel Haze’s snappy vaunting “New York”; other lists featuring singers and songwriters I especially like – Cecile McLorin Salvant, Renee Fleming, Susan Graham, Johnny Cash, Madeline Peyroux, Blind Willie Johnson, Lhasa de Sela.

I could go on and on like a rando fan – but in the spirit of my book, which aspires to channel many kinds of linguistic and emotional texture, and to offer an array of sonic shapes, I’ll end with a promise (threat?): more anon!

Maureen N. McLane is the author of several previous books of poetry, including Some Say; Mz N: the serial: A Poem-in-Episodes; and the 2014 National Book Award finalist This Blue. Her book My Poets, a hybrid of memoir and criticism, was a finalist for the 2012 National Book Critics Circle Award for autobiography.

If you appreciate the work that goes into Largehearted Boy, please consider making a donation.