« older | Main Largehearted Boy Page | newer »

August 13, 2021

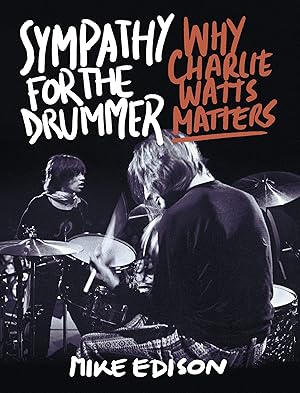

Mike Edison's Playlist for His Book "Sympathy for the Drummer: Why Charlie Watts Matters"

In the Book Notes series, authors create and discuss a music playlist that relates in some way to their recently published book.

Previous contributors include Jesmyn Ward, Lauren Groff, Bret Easton Ellis, Celeste Ng, T.C. Boyle, Dana Spiotta, Amy Bloom, Aimee Bender, Roxane Gay, and many others.

Mike Edison's Sympathy for the Drummer: Why Charlie Watts Matters is an insightful and always entertaining exploration of the Rolling Stones' drummer and his legacy both to music and the band.

Lenny Kaye wrote of the book:

"Charlie Watts is the backbone of the Rolling Stones. In this affectionate yet unflinching biography, Mike Edison shows how integral his jazz sensibility makes them a true band: keeping time, creating space, and hitting the crash cymbal at just the right moment."

In his own words, here is Mike Edison's Book Notes music playlist for his book Sympathy for the Drummer: Why Charlie Watts Matters:

A playlist to go along with Sympathy for the Drummer: Why Charlie Watts Matters could have gone off in any number of directions — there is a lot of brain-spattering, syncopated goodness in the roots of the Rolling Stones, their immediate influences (Slim Harpo, Marvin Gaye, Bo Diddley, Elmore James, Don Covay, etc.), and the dance hits that transformed them in the 1970s. I could have made a list of all things not Stones which I talk about, which is mucho, including a pantheon of drummers’ drummers — from Ray Charles’ best mambo man to Fred Below, the king of the Chicago blues drummers, to Bonham, Moon, and Bill Ward of Black Sabbath, whose jazz roots could not be covered with any amount of black hair dye. There’s also lot of finger-wagging and snark when it comes to those – guitarists and drummers — who are more interested in fellating themselves than in making love to the audience. That list never fails to get me in hot water with the prog rockers and virtuoso train spotters in the audience, and as it is, I like working as a heel. But I’ve decided to share with you a nickel tour of Charlie Watt’s astonishing trajectory behind the drum kit, featuring a few of my favorite Rolling Stones tracks that feature his particular genius, and a few baubles that helped form them, with some notes boosted in part from the book. One of the great compliments I get about Sympathy is that even the most ardent Stones fans are hearing the old music in a fresh way after reading it, and discovering new gems as they grok my nerdy footnotes and asides. Lots of chatter here, but as Charlie knows, the song’s the thing. And if it don’t got that swing… — M.E.

“Walking Shoes,” Gerry Mulligan

The stork didn’t drop Charlie on the doorstep fully formed as the Rolling Stones drummer. He was a jazz drummer slumming it to play in their blues band. But across five decades, Charlie Watts evolved from beat-keeper to shaman, his hi-hat chugging, opening and closing in counterintuitive grace, percolating with sex and voodoo, dancing with the devil, clattering with abandon and artful intent. And this is where he began his journey. “Gerry Mulligan’s “Walkin’ Shoes”—featuring Chico Hamilton’s wickedly suave brush playing— was Charlie’s radioactive spider, his gamma rays. The drums are unhurried. It is cool, not hot. Charlie says he first heard it when he was thirteen, and it was soon after that he ripped the strings off of a banjo that he had never learned to play and had at it with his own set of brushes. The rest, as they say…

“Honest I Do,” Jimmy Reed

Reed, an obsessive love interest of Brian Jones and Keith Richards, was the master of the laid-back shuffle, and his drummer, Earl Phillips, was practically seditious in his understated pulse. His songs were deceptively simple but nearly impossible to cop, not if you wanted to get it right—Phillips’s gigantic backbeat and soft shuffles on gave Reed an incalculable sort of swing, haunting, but with no uncertain drive. Phillips’s drumming is mesmerizing, not only on Jimmy Reed’s records, but also occasionally with king of the primitive modernists, John Lee Hooker, and many others, most notably on some of Howlin’ Wolf’s most hypnotic meditations—“Evil,” “Smokestack Lighting,” and the indomitable “Forty-Four,” with its heavy accent on “the one.” It’s no wonder that Charlie, too, fell in love with him. He saw what a lot of less humble cats would have sniffed at, telling DownBeat that “Keith and Brian taught me, through constant playing of Jimmy Reed. Reed and his drummer, Earl Phillips, were as sensitive as Paul Motian with Bill Evans.” Later, he would add that Phillips was one of the great jazz drummers—a ridiculous thing to say, if you were a snob, that is, but Charlie was never one of those jazz fans. And this is yet one more reason Why Charlie Watts Matters, because he knew that the real magic lived in the heart, and not in the hands.

“I Just Want to Make Love to You,” Muddy Waters

When Muddy Waters originally released this song it with the great Fred Below on drums – Charlie’s greatest influence — it was all foreplay, and for my money, still the sexiest record ever. When the Stones made their first American television appearance, in 1964, on the Hollywood Palace show hosted by Dean Martin, they delivered their own hotted-up version, and unlike the Beatles, it was very clear that Rolling Stones were not interested in holding your hand. It took them a while to learn that great R&B is almost always about anticipation and never about penetration, but there is something very powerful about announcing one’s intentions.

“Come On,” Chuck Berry

If you are suffering from any persistent memory or received wisdom that all Chuck Berry songs sound alike and are easy to play, this will change your mind. The Stones could not touch the original. In their hands — a cover of this was their very first single in 1963 — it had a pop shimmer, and a nifty tempo, but ultimately, it was Mersey-beaten half to death and a far cry from not only Chuck Berry’s version, but from the Stone’s own vision: Mick Jagger called the record “shit,” and as a group they refused to play it live. But the original was especially free form, sick, twisted, and weird, and merits a serious re listen. The drums are by the unsung Ebby Hardy, who rolls so much more than rocks, and if you play the 45rpm single at 33 1/3, it sounds like an outtake from Trout Mask Replica.

“Midnight Rambler,” Live 1972, from Ladies and Gentlemen, the Rolling Stones

By 1969, the Rolling Stones had easily graduated to the head of their class — they were something to be enjoyed, and even marveled at. But within the next couple of years, they were something to be feared, gangsters so in control of their own destiny, so unapologetic and unremitting in their attack, that anyone who was in the same line of work had to stop and question just what the hell they were doing, and if there were any real point in carrying on.

“Midnight Rambler” clocked in at anywhere between nine and thirteen minutes back in the day, depending, I suppose, on the amount of drugs Keith took before the show, and how much fun Mick was having taunting the audience, and no song in history has ever explored with such offhand grace and atavistic primitivism Delta hoodoo, city blues, and impossibly swank shuffles, and conflated so many incongruous vibes: Let’s boogie! I’m the Boston Strangler! I’m going to stab you! Suck my cock! Let’s boogie some more!

“Midnight Rambler” wasn’t so much a song as it was a crime scene. Charlie drops accents like shell casings. Mick sounds like he is choking the life out of the harmonica. He free-associates about oral sex. Strains of Chicago and the Mississippi Delta rise up like steam. The message was terrible. When the song breaks down, women are screaming. It’s hard to tell if they are turned on or scared. Likely a little bit of both. Once upon a time, there was a cute ad campaign: Would you let your daughter marry a Rolling Stone? In these years, a better question would have been: Why the hell weren’t they in jail?

“Dance (Pt. 1)” from Emotional Rescue

So how did the Rolling Stones, The Greatest Rock’n’roll Band in the World, snake by making disco records when the rock world was screaming DISCO SUCKS? Well, for one, they were really good at it. They made disco sound greasy and wet. The truth is that they had been playing great black dance music for years, and had just changed the beat with the times. They had a bad track record for chasing trends, but when they got it right, they owned it.

“Respectable,” from Some Girls Live in Texas ‘78

The Stones were uniquely suited to play disco and punk – they had been at it for years. They just called it something else. "Respectable" is as nasty as anything they had ever done – shot through with sex and drugs and outrage. The Stones’ idea of punk obviously came from within. This was their response to the brickbats and snot-nosed catcalls of them being too old to stroll because in 1978 the idea of a 30-something year-old rocker was absurd. The Stones didn’t understand punk rock, not in so much as they were sitting around listening to the Sex Pistols or the Ramones or the Damned. There was a generation gap, to be sure, and an economic one, as well. It was one thing to pal around dance clubs in Munich or Studio 54 in New York with other well-heeled celebrity cokeheads boosting riffs from the DJ, but punk rock was a youth movement, and it was never about having money, it was always about having none, and not the kind of thing entrenched millionaires were ever going to fully understand… but they came out with guns blazing. This is from the Some Girls tour, and anyone who had ever doubted that whole Greatest Rock’n’roll Band in the World thing, they were about to get stomped on. And if there are still any drummers in the house who think that Charlie Watts plays like a metronome or doesn’t bring a fully stocked arsenal to the party, try playing along with this and report back. He finds space to breathe in places where there is hardly any air, he finds jazz in the cracks between the rock and the roll, opening the hi-hat in spots that are impossible to anticipate, and the whole thing is at such a relentless tempo and intensity that only the strong will survive. But you can’t teach it, you can barely learn it, you just have to live it.

“Neighbors,” from Tattoo You

Charlie’s rim shots don’t sound so much like machine gun fire as much as they do a sprang of bullets bouncing off of marble walls during a bank heist—they ring of danger and were impossible to predict. He was never about muzzle velocity anyway—his charm lay in the danger of the ricochet.

“Had It With You,” from Dirty Work

I am going to go out on a limb and say, for the record, that the last truly great original Rolling Stones track is “Had It with You,” and I can’t think of a single Rolling Stones–penned song on any record since then that I ever really need to hear again.

Largely just Keith’s guitar, with Mick on vox and vindictive harmonica, and Charlie slugging it out, beginning with another impossibly cool snickerdoodle of a riff on the snare drum and high tom (NB they didn’t even bother with the bass track), this is a hate-filled romp broken in half with the kind of sleazy breakdown they hadn’t teased with since “Midnight Rambler." It’s amazing how this even snuck under the radar and got by the suits, it is so sonically raw-boned. Ironically, rest of the record it came from, Dirty Work, is largely considered their worst record. It sounds like the soundtrack to one of the later Rocky films —“One Hit (to the Body),” “Fight,” etc.

“Satis-faction,” from Charlie Watts Meets the Danish Radio Big Band

The remarkable thing—or perhaps the most unsurprising thing—is that Charlie Watts is the only Rolling Stone who could make a run of perfectly lovely solo records that are beyond criticism. Everyone said they loved Keith’s first record, Talk Is Cheap, but mostly everyone loves Keith, and after a few twirls, you are left wondering why you aren’t listening to the Stones. Ronnie has had some nice moments on his solo records, too, but ultimately, you are left wondering why you aren’t listening to the Faces. Or the Stones. And the less said about Mick’s dream of becoming David Bowie or Michael Jackson, the better. As for Charlie, there was no agenda. He was a jazz drummer first and foremost, and even being in the world’s most successful rock’n’roll band could not stop him from living his dream.

Mike Edison is the former editor and publisher of High Times magazine. His books include the celebrated memoir I Have Fun Everywhere I Go, the sprawling social history of sex on the newsstand, Dirty! Dirty! Dirty! and the deliciously filthy political satire Bye, Bye, Miss American Pie. More recently he collaborated with Joe Bastianich on his New York Times bestselling memoir, Restaurant Man, of which writer Bret Easton Ellis has said, “The directness and energy have a cinematic rush . . . not a single boring sentence.”

Edison has worked as a foreign correspondent for Hustler and was a high-paid gun-for-hire of the legendary Penthouse letters. He has contributed to numerous magazines and websites, including Huffington Post, the Daily Beast, the New York Observer, Spin, Interview, and New York Press, for which he covered classical music and professional wrestling. In addition, he is an internationally known musician and ferociously dedicated storyteller, and can be heard every Sunday on his show Arts & Seizures on the Heritage Radio Network. Edison lives and works in Brooklyn.

If you appreciate the work that goes into Largehearted Boy, please consider making a donation.