« older | Main Largehearted Boy Page | newer »

April 20, 2022

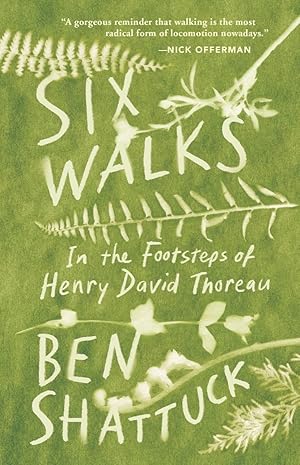

Ben Shattuck's Playlist for His Book "Six Walks"

In the Book Notes series, authors create and discuss a music playlist that relates in some way to their recently published book.

Previous contributors include Jesmyn Ward, Lauren Groff, Bret Easton Ellis, Celeste Ng, T.C. Boyle, Dana Spiotta, Amy Bloom, Aimee Bender, Roxane Gay, and many others.

Ben Shattuck's Six Walksis an insightful and meditative book inspired by the walks of Henry David Thoreau.

Publishers Weekly wrote of the book:

"Resplendent. . . . Echoing Thoreau’s brilliant reflections with his own, Shattuck distills the healing power of nature into a narrative that’s a pure pleasure to wander through. Fans of Annie Dillard will find this mesmerizing."

In his own words, here is Ben Shattuck's Book Notes music playlist for his book Six Walks:

Six Pieces of Music

Cape Cod

John Luther Adams, The Wind in High Places: I. Above Sunset Pass

Henry David Thoreau’s favorite instrument, apparently, was the Aeolian harp—an instrument played only by the wind and named after the ancient Greek god of the wind (all very fitting for a man who walked in the landscape for no less than four hours a day). Think: strings stretched over a wooden sound box, vibrated by nothing but moving air. John Luther Adams’s The Wind in High Places is a nod to Henry’s favorite sound—to the wind, and how its instrument could make the meandering, unfolding melody of this piece, with its open strings and natural harmonics. This sound is also how I think of Six Walks beginning: when I was standing in the shower before sunrise, awoken by nightmares, and seeing in my mind a young man standing alone on a vast beach. This music comes to you like a dream, and unfolds to an invitation, which is exactly what I was hoping for that morning in the shower: to leave the “constellation of grief” around me for something outside myself. The way I see it now, Henry was extending his hand from the past, saying, “Come with me” This piece has that quality of invitation, of beckoning.

Mount Katahdin

Blick Bassy, Ngui Yi

I listened to this very beautiful song by the Cameroonian singer Blick Bassy while driving north, to and through Maine, along winding coastal roads and then, eventually, inland, through endless forests of interior Maine, to Mount Katahdin. There’s something aerial about this song—the rhythmic, guitar-like wings beating through the sky, the way the whole song seems lifted aloft by Bassy’s voice (especially by his dreamy humming just after the two-minute mark). The summit of Mount Katahdin is the highest place in Maine, and the end of the Appalachian Trail. When you get up there and stand among the stones, above the tree line, you feel closer to the sky than you do to the ground. It’s a place that lifts you up and out of the dense forests; a place that puts you in the clouds. When I returned from Katahdin and drove east, back to coastal Maine, this was the song playing in the car, and it kept that feeling of flight alive.

Wachusett Mountain

Hot Chip, Melody of Love

On Wachusett Mountain, I took a couple pills of MDMA to try to feel—or, rather, short-circuit—some of the transcendent experience that Thoreau and Emerson felt and wrote about in nature. When you start reading nineteenth-century philosophers and authors, one of the first things you realize is that they had a steadfast, unshakable belief in the divine—unlike most of us these days. Going out into the woods, standing in a meadow under the sunlight, or watching a butterfly alight on a flower were all expressions of God. I felt robbed, in a way, to walk out in the landscape after the mid-nineteenth century, when it’s so much harder to believe the divine is necessarily linked to the forest or meadows or sunlight. A song like this—and so much of Hot Chip’s music—feels divine, in the way it fills you up and expands outward. It feels like taking ecstasy on a summery mountain slope.

Southwest

Jordi Savall, Prelude (Re Mineur) (Abel)

In this section of the book, I leave my house (formerly my great-grandfather’s house) and walk southwest, along the coast, to my family’s ancestral summer home, uncovering darker moments in my family history along the narrative way: infidelity, opium addiction, possible murder, young death, depression, divorce, missed love, and the loneliness of rural living. This “prelude” by Catalonian composer Jordi Savall—played on the viola da gamba—is the sound of a dark family history. A fluttering line of notes that foreshadows secrets uncovered. It’s the soundtrack I imagine for a film about a troubled and old New England family. Under the old houses and pretty ocean views is a darkness that rumbles through generations and will not, likely, be talked about.

The Allagash

Nas, It Ain’t Hard To Tell

This section is the farthest point north Thoreau traveled in his famous Maine Woods essays. Even now, it’s remote—the roads to the Allagash Wilderness Waterway are dirt, and moose and bear wander around. I went with my closest friend, John, to canoe out to the island where Thoreau waited out a thunderstorm with his good friend Edward. This section is about companionship and separation—in the ways that Thoreau knew it and the way that I have it. I thought a lot about John, about how close we once were, and how we now only see each other a few times a year. I first met him in San Francisco, over ten years ago, and ever since our lives have seemed to be braided, in a way. This is the song he played back then, over and over, when I first met him, in his apartment in The Mission and while driving in his old Volvo. And so, this is the song of the Allagash for no other reason than that it is a dedication to him.

Cape Cod, Again

Gillian Welch, I Dream A Highway

In Cape Cod, Again, I return to a place I’d visited alone years earlier, when I was desperately running away from grief. This time, I’m with my fiancée, who is six months pregnant with our daughter. Life was different for me when I went back—more stable, with companionship, and the questions I had had about my future were comfortably answered. What I was looking for in the landscape of Cape Cod on my first trip—to get away, to be alone, to follow someone else’s habits for a few days—had disappeared. I felt no urgency to get out into the wild. I wanted to, well, stay home. I was done with Thoreau’s walks. It was sad to, in a way, leave Thoreau behind. To say goodbye to this invisible companion. This second visit to Cape Cod was about leaving him, and my grief, behind, on the beaches that I’d visited years earlier. The waves, the dunes, the sand, the wind, and the clouds—all of it looked the same. But I was different. Gillian Welch’s I Dream A Highway could be interpreted as many things, if you look closely at the lyrics, but for me, I’ve heard this fourteen-minute, meandering song as a blissful return to love.

Ben Shattuck, a former Teaching-Writing Fellow and graduate of the Iowa Writers' Workshop, is a recipient of the PEN/Robert J. Dau Short Story Prize and a 2019 Pushcart Prize. He is the director of the Cuttyhunk Island Writers' Residency and curator of the Dedee Shattuck Gallery. His writing can be found in the Harvard Review, The Common, the Paris Review Daily, Lit Hub, and Kinfolk Magazine. He lives with his wife and daughter on the coast of Massachusetts, where he owns and runs a general store built in 1793.

If you appreciate the work that goes into Largehearted Boy, please consider making a donation.